🌿Wild Ones #48: Environmental Communication Digest

Environmental Keyword: 'The Captivity Paradox' and the Modern Zoo + A Green Approach to Linguistics + Visualizing Climate Change + More!

Hi everyone, welcome back to Wild Ones, a weekly digest by me, Gavin Lamb, about news, ideas, research, and tips in environmental communication. If you’re new, welcome! You can read more about why I started Wild Ones here. Sign up here to get these digests in your inbox:

🌱Environmental Keyword

‘The Captivity Paradox’

“The economic significance of charismatic animals to zoos has implications for animal welfare. The central, tragic paradox to this commodification of charisma is that many of the animals that are so captivating to zoo-going publics are those that fare least well in conditions of captivity. This is the captivity paradox.” –– Jamie Lorimer, in Wildlife in the Anthropocene: Conservation after nature

Environmental writer Emma Marris, author of a forthcoming book I’m really looking forward to – Wild Souls: Freedom and flourishing in the non-human world – has just published a new opinion essay in the NYTimes (June 11) arguing that keeping wildlife captive for life in zoos is unethical.

In the essay, Emma Marris makes the case for phasing out modern zoos centered on displaying captive wildlife for human ‘edutainment.’ Some conservation-oriented zoos could transition to wildlife-centered “refuge-zoos,” says Marris, which “could become places where animals live. Display would be incidental.” But the vast majority of zoos are no longer worth the moral cost of captivity.

Tracing the origins of the modern zoo to 19th-century European public zoos, modeled in particular on the London Zoo, Marris examines a shift in public discourse about the role of zoos in society: “Zoos shifted just slightly from overt demonstrations of mastery over beasts to a narrative of benevolent protection of individual animals.”

This shift from zoos as displays of human mastery to benevolent wildlife protectors led to the mainstream idea today that zoos are essential tools in wildlife and biodiversity conservation. There are two key discourses zoos embraced in “actively rebranding themselves as serious contributors to conservation.”

Breeding captive wildlife as insurance against extinction: “Zoo animals, this new narrative went, function as backup populations for wild animals under threat…”

Displaying captive wildlife as conservation ambassadors for their species: Marris interviews Dan Ashe (@DanAshe), president of the Association of Zoos & Aquariums. He tells Marris that the overall aim of zoos is to instill in visitors a “sense of empathy for the individual animal, as well as the wild populations of that animal.”

This second point is similar to the wildlife tourism discourse I often hear in my own research on the sea turtle tourism industry in Hawai‘i. This is the idea that tourists’ encounters with charismatic wildlife are an important conservation tool for getting people to actually care about wildlife and the natural world. (See Powell & Ham 2008 for example).

Even for conservation-minded zoos, staging close encounters with wildlife ‘on display’ is key to creating the perfect combination of entertainment and education (or “edutainment”): “Proximal, embodied encounters with charismatic fauna are the elixir here—from the Serengeti to the zoo,” writes environmental geographer Jamie Lorimer. “Their evocative, promissory images populate marketing materials” and “Wildlife managers go to great lengths to ensure bountiful and visible populations (at least within the bounds of the private spaces in which they might be viewed)….”

Many of the commenters on Marris’ NYtimes article also made the argument that “zoos help us care.” For example, Tom from Wisconsin replied: “You don't care about what you never see. We do not care about people in far off lands, do you expect we would care about their animals? Zoos do bring animals for us to see. Zoo bring animals for us to care about. With out exposure who cares if a species goes extinct. Zoos help us care” (note: typos in original post).

But for Marris, it’s not just that it’s unethical to hold charismatic wildlife captive so they can function as conservation ambassadors for the free-roaming members of their species (although that’s a key line of her argument). She’s also skeptical there is even a link between visiting a zoo for a day and subsequently adopting life-long conservation attitudes:

“People don’t go to zoos to learn about the biodiversity crisis or how they can help. They go to get out of the house, to get their children some fresh air, to see interesting animals. They go for the same reason people went to zoos in the 19th century: to be entertained.”

If a zoo were modeled first on serving the spatial needs of wildlife, rather than those of humans – such as Marris’ proposal to transition zoos to zoo-refuges where “display would be incidental” and animals could live out their lives according to their own spatial needs – then the very commodity zoos depend on for their existence would likely slip away into the less controlled, less displayable wild spaces of a more spacious refuge. This is the ‘captivity paradox’ zoos face.

There is another layer to the ‘captivity paradox’: the wildlife most sought out by zoos are often the ones that struggle most with captivity. This is how Jamie Lorimer describes the ‘captivity paradox’ (to expand on a quote of his I mentioned at the beginning):

“The central, tragic paradox to this commodification of charisma is that many of the animals that are so captivating to zoo-going publics are those that fare least well in conditions of captivity. This is the captivity paradox…Although the living conditions of zoo animals have improved significantly in recent years, it is difficult—even with a sympathetic take on zoos’ claims for conservation—not to see these charismatic icons as sacrificial victims, performing their captive, commodified, and simulated lives so that other (often less charismatic, free-ranging) life might persist.”

So, what might a solution to zoos’ ‘captivity paradox’ look like? I’m really curious to hear how any readers out there remember their experiences at zoos, how this experience influenced your environmentalism (or not), and how/if zoos should be radically transformed. Emma Marris has one interesting proposal: Phase-out the breeding of captive wildlife in zoos (except when there are plans to reintroduce near-extinct species back into the wild) and then, turn zoos into botanical gardens:

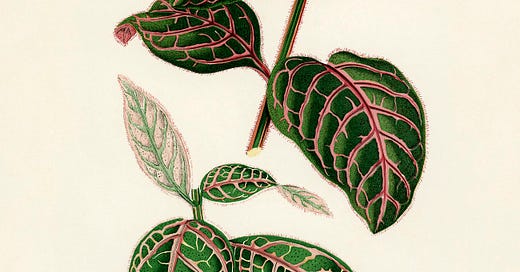

“As an avid fan of botanical gardens, I humbly suggest that as the captive animals retire and die off without being replaced, these biodiversity-worshiping institutions devote more and more space to the wonderful world of plants.”

– Emma Marris, in Modern Zoos Are Not Worth the Moral Cost.

📚 What I’m reading

The Bison and the Blackfeet: Indigenous nations are spearheading a movement to restore buffalo to the American landscape. By Michelle Nijhuis in Sierra: “The species biologists call Bison bison is known in the Blackfoot language as iinnii, in Arapaho as bii or heneecee, and in any Indigenous plains language as a synonym for life itself.”

🎧 What I’m listening to

At the Mouth of the Menominee River: A Conversation with Anahkwet (Guy Reiter) on the Edge Effects Podcast.

📰 News and Events

May 26 was good. The news made it bad: News outlets that covered the big climate wins of May 26 overwhelmingly chose to center the oil industry’s plight over the planet’s progress. In Heated by Emily Atkin.

Introducing: Down to Earth, our new project on the biodiversity crisis. By Eliza Barclay and Brian Anderson in VOX: “Why a reporting initiative on the science, politics, and economics of an ecological catastrophe is so badly needed.”

A hallucinogenic toad in peril: How a Sonoran Desert species got caught up in the commodification of spiritual awakening. By Jessica Kutz in High Country News.

The Keystone XL Pipeline Is Dead. Next Target: Line 3. By Bill McKibben in NYTimes.

Nuclear bomb detectors uncover secret population of blue whales hiding in Indian Ocean: Scientists found recordings of their unique song dating back almost 20 years. By Harry Baker, in Live Science.

Communicating COVID 19 – Trials, Challenges and Lessons. Live Virtual Event (Zoom): Wed, June 23, 2021: 19:30 to 21:30 (Irish time I think).

📚 Research

‘Amber Alert’ or ‘Heatwave Warning’: The Role of Linguistic Framing in Mediating Understandings of Early Warning Messages about Heatwaves and Cold Spells. By Chris Tang in Applied Linguistics (ahead of print).

A Bibliography of Trash Animals from Discard Studies: “Gulls. Pigeons. Rats. Lice. These supposed ‘trash animals’ live alongside waste, filth, disease, ruination and decay. Because of their affiliation with discards, ‘trash animals’ are often framed as dirty and subjected to vilification, violence and even killing…”

How Green Became Good: Urbanized Nature and The Making of Cities and Citizens. By Hillary Angelo, University of Chicago Press: “In How Green Became Good, Hillary Angelo uncovers the origins and meanings of the enduring appeal of urban green space, showing that city planners have long thought that creating green spaces would lead to social improvement.”

💡 Ideas

It takes a wood to raise a tree: a memoir. An ecologist traces forests’ support networks — and finds parallels in her own life. By Emma Marris in Nature.

The Insidiousness of Wiggle Words: When it comes to the climate crisis, the G7's statement says nothing of substance—just like everyone else. By Brian Kahn in Earther.

Native Species or Invasive? The Distinction Blurs as the World Warms, by Sonia Shah, in Yale Environment 360:

“With thousands of species on the move as the climate changes, a growing number of scientists say that the dichotomy between native and alien species has become an outdated concept and that efforts must be made to help migrating species adapt to their new habitats.”

How stressed out are factory-farmed animals? AI might have the answer.

The promise and perils of using facial recognition technology on animals. By Laura Bridgeman in Vox:“Pigs can never be happy in factory farms,” says Lori Marino, director of the Kimmela Center for Animal Advocacy and an expert in animal behavior who co-authored a study on pig cognition and emotion. To Marino, “a CAFO [concentrated animal feeding operation] is so far from what a pig needs to thrive that it could not be a place that would make a pig happy or content. They are not designed for pig happiness.”

Reclaiming Native Knowledges Through Kelp Farming in Cordova, Alaska. By Jen Rose Smith in Vogue.

💬 Quotes I’m thinking about

“It is easy to think that if we protect species and ecosystems, then we will be protecting animals too. But while protecting species and ecosystems might help, it is not enough. Animals are more than parts of a whole, like drops of water or grains of sand. They are living, breathing, thinking, feeling individuals. What some animals need differs from what other animals need, and what animals need individually differs from what they need collectively.”

– Jeff Sebo, Clinical Associate Professor of Environmental Studies and Director of the Animal Studies M.A. Program at New York University. In All we owe to animals, an essay in The Conversation.

✏️From the archive

Thanks so much as always for your interest in my work, and if you found this digest useful, please consider sharing with others who might find it interesting too😊 I'd also love to hear from you. Leave a comment to let me know what you think about this digest, what areas of environmental communication you’re involved in/most interest you, or anything you’d like to see more of in Wild Ones:)

Please keep up the good work, Gavin. Perhaps this aricle might interest you Richard J. Alexander On the hegemonic power of the pandemic discourse. International Journal of Business and Applied Social Science (IJBASS) E-ISSN: 2469-6501 VOL: 7, ISSUE: 6 June / 2021. [http://dx.doi.org/10.33642/ijbass.v7n6p5]