🌿Wild Ones #79: Environmental Communication Digest

Environmental Keyword: Discourses of Climate Delay + Snail Stories in Times of Extinction + Amy Westervelt on 'the real free speech threat' + More!

As I’m sure many of you have been as well, I’ve been following news of the devastating Lahaina, Maui fires this week. If you would like to help, there are many organizations providing aid, a local community organization I suggest is the Hawai‘i Community Foundation’s Maui Strong Fund.

Hi everyone, welcome back to Wild Ones, a (trying-to-be) weekly digest by me, Gavin Lamb, about news, ideas, research, and tips in environmental communication. If you’re new, welcome! You can read more about why I started Wild Ones here. Sign up here to get these digests in your inbox:

🌱Environmental Keyword

Discourses of Climate Delay

“Discourses of climate delay’ pervade current debates on climate action. These discourses accept the existence of climate change, but justify inaction or inadequate efforts. In contemporary discussions on what actions should be taken, by whom and how fast, proponents of climate delay would argue for minimal action or action taken by others. They focus attention on the negative social effects of climate policies and raise doubt that mitigation is possible.”

— William F. Lamb, Giulio Mattioli , Sebastian Levi , J. Timmons Roberts , Stuart Capstick , Felix Creutzig, Jan C. Minx , Finn Müller-Hansen , Trevor Culhane and Julia K. Steinberger (2020). Discourses of Climate Delay. In Global Sustainability.

“Of all the messaging geared toward delaying action on climate, or assurances that the fossil fuel industry has a grip on possible solutions, [William] Lamb and other authors agreed that one theme was far more prevalent than the rest: ‘the social justice argument.’ This strategy generally takes one of two forms: either warnings that a transition away from fossil fuels will adversely impact poor and marginalized communities, or claims that oil and gas companies are aligned with those communities. Researchers call this practice ‘wokewashing’.”

— Amy Westervelt, “Big oil’s ‘wokewashing’ is the new climate science denialism.” In The Guardian (2021).

In June, I posted a Substack ‘note’ (a Twitter-like feature) with the following quote from the 2021 book Pollution is Colonialism by Max Liboiron:

“A core scientific achievement in the permission-to-pollute system was the articulation of assimilative capacity – the theory that environments can handle a specific amount of contaminant before harm occurs…The threshold theory of pollution differentiates between contamination, as the mere presence of a pollutant, and pollution, as the manifestation of (scientifically!) demonstrable harm by pollutants when metabolism is overwhelmed. Assimilative capacity is based on land relations that strip away the complexities of Land - including relations to fish, spirits, humans, water, and other entities – in favour of elements relevant to settler and colonial goals for using the water as a sink, a site of storage for waste.”

~ Max Liboiron (2021). Pollution is Colonialism. Duke University Press. (pp. 39-40)

After posting the quote above on Substack Notes, I received a comment claiming that connecting pollution to colonialism was ‘woke verbiage.’

What is this anti-‘woke verbiage,’ and why do some people (even some linguists), claim we should be wary of it? Why are some conservative presidential candidates claiming that concern about climate change is part of a ‘dangerous woke ideology.’ And what are the communication tactics at work when, for example, a presidential candidate on the right invokes the idea of ‘wokeism’ to discredit the climate justice movement? A few years ago, reporter Aja Romano wrote a in depth multimedia essay in Vox on the “history of wokeness,” exploring both the origins of the term ‘woke’ and how it became a ‘bipartisan’ keyword in U.S. politics following the emergence of the Black Lives Matter movement in the wake of Michael Brown’s killing by a police officer on August 9, 2014. While “‘woke’ and the phrase ‘stay woke’ had already been a part of Black communities for years,” Romano writes, since 2014:

“…‘woke’ has evolved into a single-word summation of leftist political ideology, centered on social justice politics and critical race theory. This framing of “woke” is bipartisan: It’s used as a shorthand for political progressiveness by the left, and as a denigration of leftist culture by the right.”

In recent years, I’m seeing some conservative politicians and climate contrarians invoke the idea of anti-‘wokeism’ to denigrate the climate movement, and the environmental movement more broadly, as the ‘gravest threat to American democracy’ (by which they seem to mean ‘a threat to American capitalism’). I wrote this post to help me make sense of this ‘anti-woke’ discourse, which I understand as an emerging discourse of climate delay. It took me quite a few more words than planned to make some sense of it for myself, so at any point, please feel free skip to the regular digest below:)

“a radical and dangerous wokeism…”?

One of the reasons I wanted to make sense of how a discourse of anti-‘wokeism’ is being invoked in discourses of climate delay is because of an academic exchange that’s been in the back of my mind since I first encountered it last year. The exchange was between the applied linguists Bernard Spolsky (1932-2022) and Alastair Pennycook and appeared in the inaugural volume the journal Educational Linguistics (2022). Spolsky asks, “Do we need critical educational linguistics?” In asking this question, he wonders if the label ‘critical’ is unnecessarily applied to research fields, especially in light of developments of a ‘radical movement’ in academia —and he quotes this article in the Economist —where “critical added to a field seems to include it in ‘left-liberal identity politics, social-justice activism or, simply, wokeness.’” Worried about this ‘radical left woke’ movement taking over academic debate, Spolsky argues that “the question we need to ask is, does the addition of “critical” to ‘bilingual education’ and ‘language policy’ do more than add a fashionable term?” Spolsky concludes that ‘there is room’ to usefully add the label ‘critical’ (such as efforts by applied linguists to contest the anti-bilingual movement in the U.S. and discriminatory language policies like it around the world), “while remaining uncomfortable with the terminological connection to a radical and dangerous wokeism…” (p. 14).

What is this ‘radical and dangerous wokeism’ that Spolsky is worried about? Spolsky argues that anti-racist education “suffers from the semiotic narrowing of the term ‘racism’ noted by McWhorter (2021).” As Pennycook points out in his response to Spolsky, the linguist/cultural critic John McWhorter, who Spolsky draws on, compares wokeness to a religion, or rather, claims it is actually a religion:

“I do not mean that these people’s ideology is ‘like’ a religion. I seek no rhetorical snap in this comparison. I mean that it actually is a religion…An anthropologist would see no difference in type between Pentecostalism and this new form of antiracism” —McWhorter, Woke Racism (2021).

So wokeism, it appears, is a kind of quasi-religious movement for Spolsky that should make us wary of research that uses the label ‘critical’ as a code for ‘woke.’ Alastair Pennycook offers a helpful, critical response to Spolsky’s claims that I think has wider significance for researchers in environmental communication. First, Pennycook points out that “the invocation of ‘wokeism’ is, first of all, an unfortunate step that does little more than warn conservative commentators against “leftist” politics and “social-justice activism.” (p. 2) Pennycook goes on to argue that,

Reducing critical work to a notion such as wokeism is a perilous move. What is this so-called wokeism of which we should be so wary? The term has a long history (with African American origins) but was only added to the Oxford English Dictionary in 2017, meaning “well informed” or “alert to racial or social discrimination and injustice” (OED 2017). What this definition fails to capture, however, is the ways that reactionary forces have transformed the use of the term from “being alert to social injustice” to referring to “a person who affects a false, superficial and politically correct morality” (Rhodes 2022: 2). Indeed, it could be argued that the term wokeism has come to replace the equally problematic “political correctness”. Both are terms used to denigrate concerns about social inequality by disparaging those concerned on the basis that they are adhering to a set script or behaving without sincerity: “To be woke is cast as a form of insincere self-righteousness” (Rhodes 2022: 3).

In his article, Spolsky seems to use the label ‘wokeism’ to describe the ‘insincere self-righteousness’ of social justice activism (which he says is “largely restricted to ‘cancelling’” others) and worries that this ‘left-liberal identity politics, social-justice activism or, simply, wokeness” is what the label “….‘critical’ added to a field seems to include…”

As Pennycook points out, however, “Undermining serious political causes by calling them woke is a way of diluting resistance to the political status quo. Such woke name calling serves a definitively conservative function: it shields existing power structures from criticism so that they do not face any real challenge” (Rhodes 2022: 7, cited in Pennycook, pp. 3-4). He concludes that,

“To invoke the idea of wokeism is therefore to draw on conservative and generally non-academic discourses that aim to undermine those engaged in forms of “social-justice activism”, labelling this as “identity politics” (another problematic term), and attempting to discredit such work by appeal to a set of labels that circulate in discourses of reactionary populism” (p. 3).

“The ‘anti-woke capitalism’ movement”

More recently, this ‘anti-woke’ discourse is invoked to undermine the climate movement. The climate journalist Emily Atkin, for example, writes about an emerging anti-‘woke investing’ movement that especially targets companies hostile to the fossil-fuel industry. As she writes, “A new trend is sweeping conservative America. It’s called the anti-ESG movement, or “anti-woke capitalism” movement, and it’s one of the biggest emerging barriers to corporate action on climate change.” Atkin goes on to write,

“the anti-ESG movement is the same as it ever was: a political effort to delay climate action led by fossil fuel industry propagandists. It follows the classic playbook of climate disinformation by trying to “both sides” the idea of climate risk [e.g. both climate denial and climate delay]. In other words, the overall tactic is to use a collection of seemingly competing discourses that all achieve the same goal: climate action delay.”

Consider the rhetoric coming from conservative U.S. presidential candidate Vivek Ramaswamy. In a profile of the candidate in the New Yorker, Sheelah Kolhatkar writes about the “CEO of anti-woke” and his mission against ESG investing:

“To Ramaswamy, such corporate do-gooderism—and especially environmental, social, and governance investing, known as E.S.G.—is a smoke screen designed to distract from the less virtuous things that companies do to make money. Amazon donates to organizations that aid Black communities while firing workers trying to unionize.”

On the surface, this appears to not be such a big departure from similar critiques of ‘wokewashing’ coming from the American political left which call out corporations’ disingenuous ‘virtue signaling’ to conceal their commitment to upholding the status-quo (see the section below). But at the same time, “Ramaswamy’s twist on the familiar critique” of wokewashing is that it poses an existential threat to ‘American democracy,’ by which Ramaswamy really means a threat to unbridled free-market capitalism. As Kolhatkar puts it,

“…he calls this kind of socially conscious investing—not political corruption or dark money, not election denialism, not disinformation—the gravest danger that American democracy faces today.”

In an interview on CNN with Ramaswamy where he was questioned about what he means by ‘wokeism,’ I found his response revealing in the way he connects ‘wokeism’ with the climate movement. For Ramaswamy, in the vacuum of a ‘missing national identity,’ he sees a new ‘climate religion’ filling this American identity void. The most dangerous thing about this new ‘climate religion’ is its ‘anti-growth’ ideology, he says, which now presents the biggest threat to the United States as an “a-political sanctuary of capitalism.” In other words, fossil-fueled, growth-addicted capitalism isn’t ideological or political, but anything that questions it is!

‘Big Oil Wokewashing’

Linguistic anthropologists deandre miles-hercules and Jamaal Muwwakkil recently critiqued the phenomenon of ‘virtue signaling’ which they define as

“…the action or practice of highlighting one’s morality through the use of language and other signs that index superficial alignment with progressive sociopolitical values. Anti-racist posturing— virtue signaling par excellence— comprises a genre that recruits the performativity of language to fashion speakers’ intersubjectivity in staunch opposition to white supremacy”

The authors write that the practice of virtue signaling has enabled the “Increasing commodification of progressive language in public discourse over the past four decades.” This commodifying communication practice, they continue, “has resulted in users’ indexical alignment1 with anti-racist politics becoming unmoored from expectations of legitimate action toward dismantling white supremacy” (p. 267).

Drawing on a similar critique, the philosopher Olúfẹ́mi O. Táíwò examines the notion of ‘woke capitalism’ as a form of ‘corporate virtue signaling.’ In his work, Táíwò explores how corporations are increasingly using ‘woke language’ as a means to ‘capture identity politics’: that is, use language that appears sensitive to structural racial and gender inequalities in society while not doing much to actually change them, or indeed, cynically using such language to thwart efforts aimed at addressing these inequalities. As Táíwò argues, “claiming to care about marginalized voices can be a way to maintain wealth and power for the elite.” In his recent book Elite Capture: How the Powerful Took Over Identity Politics (And Everything Else), Olúfẹ́mi O. Táíwò highlights two superficial ‘woke’ communication strategies used to avoid or even prevent legitimate (woke) action: 1) ‘symbolic identity politics’ and 2) corporate ‘rebranding’:

“…despite differences in local context, when people around the world rose up against the police terror and violence to which they have been subjected for hundreds of years, it was immediately clear that something global was at stake. The response from governing elites was equally immediate: the World Bank established a “Task Force on Racism,” and the United Nations, under pressure from the entire African Union bloc of fifty-four countries, agreed to launch a yearlong inquiry into anti-Black racism. Two strategic trends in the response quickly became clear: the elites' tactic of performing symbolic identity politics to pacify protestors without enacting material reforms; and their efforts to rebrand (not replace) existing institutions, also using elements of identity politics.”2

Similar communication strategies appear to be used to ‘wokewash’3 big oil too, as climate journalist Amy Westervelt examines. As she puts it, “A casual social media user might get the impression the fossil fuel industry views itself as a social justice warrior, fighting on behalf of the poor, the marginalized, and women – at least based on its marketing material in recent years”:

“This strategy generally takes one of two forms: either warnings that a transition away from fossil fuels will adversely impact poor and marginalized communities, or claims that oil and gas companies are aligned with those communities. Researchers call this practice ‘wokewashing’”

Westervelt cites research on climate delay tactics which examine ‘wokewashing’ as one of several communication strategies big oil companies use to delay climate action, “from focusing on what individual consumers should be doing to reduce their own carbon footprints to promoting the ideas that technology will save us and that fossil fuels are a necessary part of the solution.”

For instance, Westervelt examines how oil companies increasingly enlist a social justice rhetoric to argue that regulating fossil fuels will devastate marginalized communities: “The social justice argument is the one we’re seeing used the most,” one of the researchers Westervelt interviews says. Wokewashing is thus part of this general shift in communication used by Big Oil (aka the six largest oil and natural gas producers: BP, Chevron, Eni, ExxonMobil, Shell, and TotalEnergies). Today, these companies outspend their climate denialism advertising with ‘climate delay’ communication tactics by a factor of 5 or 10 to 1. In sum, climate delay communication tactics focus not so much on anti-climate science and denial, but on “pro-fossil fuel propaganda – campaigns that remind people over and over again about all the great things oil companies do, how dependent we are on fossil fuels, and how integral the industry is to society.”

“These things are effective, they work,” says another researcher of climate delay tactics, “So what we need is inoculation – people need a sort of field guide to these arguments so they’re not just duped.”

‘Climate Alarmism’ + ‘Wokeism’ = ‘Climatism’

Those invoking discourses of climate delay seem to have no problem using a contradictory set of both ‘wokewashing’ and ‘anti-woke’ communication strategies. For instance, rather than using ‘wokewashing’ to insincerely portray oneself (or one’s corporation) as concerned about climate justice, another tactic is to undermine those sincerely concerned about climate justice by disparaging them as ideologically compromised ‘woke climate alarmists’ or ‘climatists.’

Take Mike Hulme, a professor of human geography at Cambridge, who writes in his recent book Climate change isn’t everything (I imagine in reference to Naomi Klein’s 2014 climate book, This Changes Everything):

“the ideology – the settled belief – that the dominant explanation of all social, economic and ecological phenomena is a human-caused change in the climate. Complex political, socio-ecological and ethical problems and challenges come to be regarded as only being solved or adequately dealt with by first arresting the human causes of changes in climate.”

This of course is a gigantic, Stay Puft Marshmallow-size straw man. I’m not aware of a climate justice movement that is actually advocating we not address any social challenge like poverty, human rights, democratic reform or hunger before climate change is ‘fixed.’ The whole point of climate justice is a recognition that the climate crisis is a ‘threat-multiplier,’ that exacerbates (not cause) already existing colonial and capitalist histories of interwoven social and ecological exploitation, and thus requires interwoven solutions that address these histories of injustice. But Hulme’s idea of ‘climatism,’ as a label for a form of ‘environmental wokeism’ that seems to be gaining traction in reactionary anti-woke political discourse, erases this historical argument in order to claim that the climate movement is beholden to the belief that climate change is the root ‘cause’ of the all world’s problems.

Accusing others of ‘climatism’ is a key climate delay communication strategy that informs the anti-woke language deployed by other popular climate delay commentators like Michael Shellenberger, Bjorn Lomborg,4 and Roger Pielke Jr. On the one hand, they all say that climate change is real, but that it’s not a crisis worth worrying about. On the other hand, they portray their own climate delay position as a-political and ideology-free (just like Ramaswamy’s defense of the ‘a-political sanctuary of capitalism’) while claiming to ‘debunk’ environmentalists as ideologically compromised ‘alarmists’ who mistakenly attribute climate change as the primary cause of all the world’s problems. As I mentioned above, despite the arguments that climate activists are actually making about climate change as an exacerbating pressure on pre-existing social and ecological challenges—not a singular cause—doesn’t really matter because it’s proving to be a useful communication tool in the politics of climate delay.

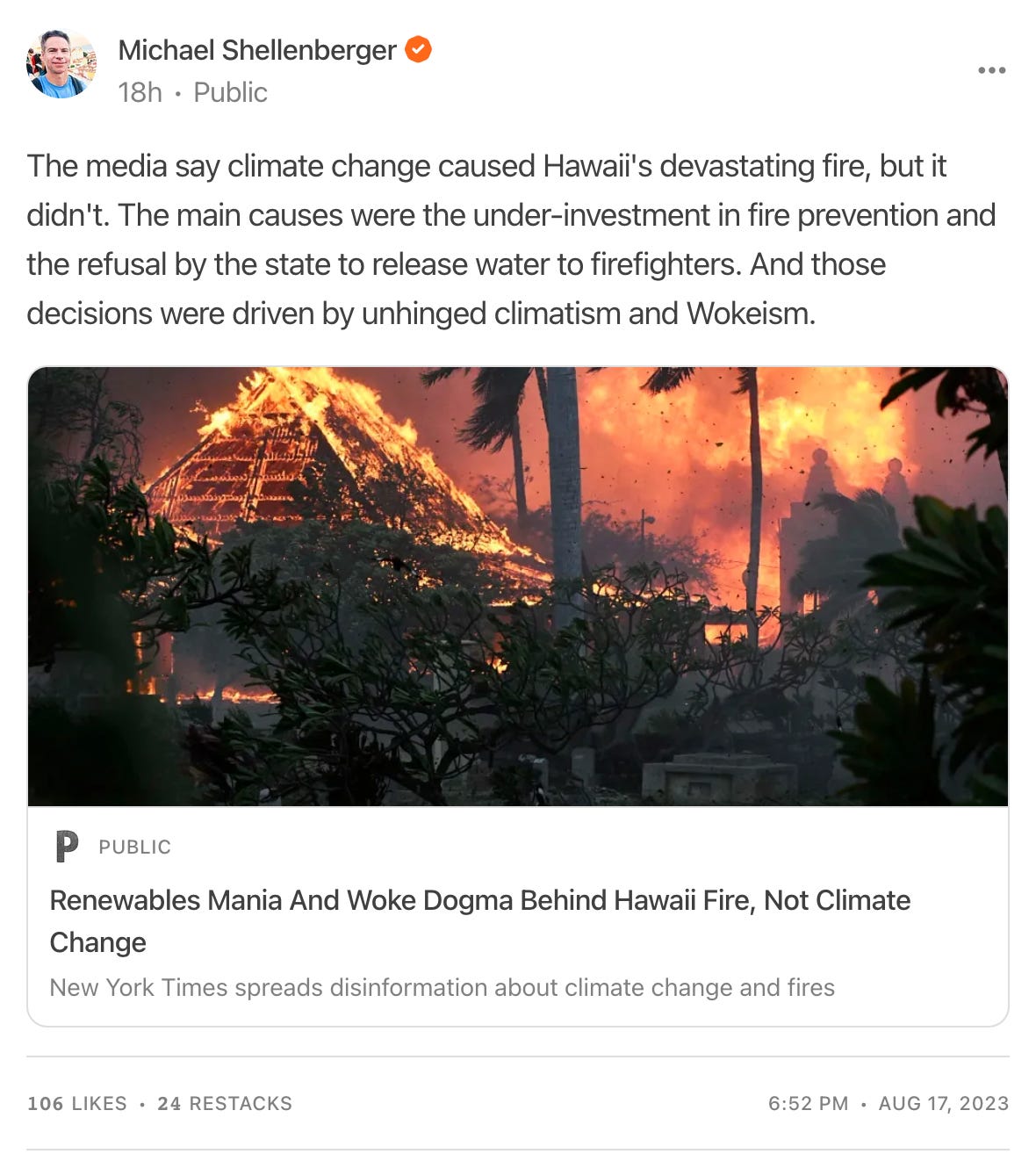

For instance, the Substack Note below is a good example of how this anti-woke discourse of climate delay is being deployed, in this case, by Michael Shellenberger, the co-founder of the ‘post-environmentalist’ Breakthrough Institute. He has been a leading alarm-raiser against what he has called ‘climate alarmism,’ but more recently seems to enlist Hulme’s anti-woke ‘climatism’ discourse to make a similar argument:

Shellenberger argues that the “New York Times spreads disinformation about climate change and fires” referring to the NYTimes article: How Climate Change Turned Lush Hawaii Into a Tinderbox. The NYTimes article claims climate change caused the fires in Maui, Shellenberger argues. Thankfully(!) Shellenberger is here to debunk this ‘woke climatism’ for us and reveal its mistaken ‘causation’ argument. An important discussion can be had about how NYTimes fails to report on climate change, but in this case, the NYTimes article doesn’t appear to say what Shellenberger claims it says. The article describes a host of factors that climate change ‘amplified’ from “declining rainfall,” “and “invasive species” to histories of “longstanding sugar cane farms [that] stopped operating around the 1990s [and let] the land stopped getting irrigated.” And in regards to Hurricane Dora that passed south of Maui during the fires which contributed to extremely high winds of more than 60 miles per hour the day, the NYTimes article states that “It’s difficult to directly attribute any single hurricane to climate change.” Shellenber goes on to grossly misrepresent water conflicts in Lahaina to cynically serve his ‘anti-woke’ communication campaign against ‘climatism.’5

Seeming to take a cue from Shellenberger’s climate delay playbook, a contrarian article from ABCNews published a story with the headline “Why climate change can't be blamed for the Maui wildfires,” hopping on a similar ‘climatism’ straw man that aims to ‘debunk’ the position of climate change causation. ABCNews eventually changed the title of that article to “Why climate change can't be blamed entirely for the Maui wildfires.” In a tweet (or Xeet?), climate reporter Emily Atkin clarifies some of the issues with the ABCNews title:

The emergence of ‘anti-woke post-environmentalism’

In their article on the discourse of ‘post-environmentalism,’ political ecologists Giorgos Kallis and Sam Bliss trace the history of the ‘Breakthrough Institute,’ “a communication project developed by two directors of PR firms, Michael Shellenberger (who now seems to no longer be affiliated with institute) and his colleague Ted Nordhaus. Disillusioned with the environmental movement, they sought to advance a ‘post’ environmentalism that embraced the power of technology to address the world’s problems without interfering with growth-based business-as-usual. Their vision came to be known as the ecomodernist movement. Basically, we will simply grow out of our environmental problems “by decoupling human development from environmental impacts,” a feat made possible through human ingenuity and technological advance. Surprisingly to me, an important figure that inspired Shellenberger and Nordhaus in their development of the Breakthrough Institute as a post-environmental communication hub was the linguist George Lakoff and his notion of ‘environmental framing.’ As Lakoff succinctly put it in a famous 2010 essay on the concept of ‘environmental framing’,

“The importance of communication in politics has not been recognized sufficiently by environmentalists, and by progressives in general.” In particular, Lakoff argued, that “progressives need a much better communications system. In addition to serious framing research institutes, such a system needs training facilities, a system of spokespeople in every electoral district, and bookers to get them booked in the media.”

And building a ‘framing institute’ that steers the climate policy conversation in an ecomodernist direction is exactly what the Breakthrough Institute sought to do. However, the framing strategy Shellenberger and is collaborator Ted Nordhaus pursued was not to reframe progressive environmental values to make them more politically persuasive to the right, as Lakoff intended, but instead to “reframe conservative preferences for nuclear power, big technologies, and GMOs as green and progressive. Post-environmentalists, one might conclude, won the framing at the cost of the content,” write Kallis and Bliss.

Kallis and Bliss go on to argue that the post-environmentalist critique of traditional conservation makes some legitimate points:

Shellenberger’s and Nordhaus’ “critique was right in many respects: conservationists' obsession with pristine nature neglected working people; professional greens wasted their energy lobbying in legislative corridors for market-based solutions; climate groups inflated the promises of efficiency.”

Mixing legitimate criticisms of traditional environmentalism and conservation into their ‘anti-woke’ messaging is central to how the post-environmentalist frame appears to work. Crucial, however, is in how Shellenberger uses this mixed frame to paint all kinds of environmentalists as a homogenous group of dangerous, ideologically captured ‘alarmists.’ As Kallis and Bliss put it, “Gradually,” through their personal confrontations with various types of environmentalists, the post-environmentalists of the Breakthrough Institute became specialists in debunking environmentalism.”

Kallis and Bliss go on to suggest that the early ambitions of the Breakthrough Institute to create dialogue around arguments for transforming environmentalism into a “climate change is no big deal” philosophy” encountered some hiccups:

“…despite the intention to establish Breakthrough as a venue for dialogue, the Lakoffian framing tactics that [Nordhaus and Shellenberger] made explicit in [their manifesto ‘The death of environmentalism’] caused unproductive exchanges. Following the conservatives' example, N&S invited polemical engagements with critics. They pushed detractors to deny their message, presumably heeding Lakoff's insight that the more you get people to react to your elephant, the more everyone thinks of your elephant. Post-environmentalists frame positive messages like ecomodernism, eco-pragmatism, and environmental progress and then critics must argue against these good things, unwittingly diffusing postenvironmentalist ideas in the process. To contest post-environmentalists, you must respond with counterframes, defending your reality against theirs.”

And this, I think, is the core issue I’m trying to grasp at here in this already far-too-long post (thank you for reading if you’ve made it this far!). In the ‘woke-alarmist’ rhetoric of Shellenberger and similar climate contrarians, the only real climate truth is the one that fits comfortably in the ‘a-political sanctuary of capitalism,’ so transparently put by the conservative presidential candidate Vivek Ramaswamy. So, from this perspective, any view that challenges this self-declared ideology-free vision of the world is by its very nature ideologically compromised ‘wokeism.’ The French anthropologist Bruno Latour probably became concerned with a similar observation when he made an early departure from the Breakthrough Institute as an honorary fellow there, but only after declaring in a final presentation to the institute why Shellenberger’s and Nordhaus’ ecomodernist vision was so deeply misguided. As he said to the audience at the Breakthrough Institute that day in 2015:

“To me, [ecomodernism'] sounds much like the news that an electronic cigarette is going to save a chain smoker from addiction. A great technical fix which will allow the addicted to behave just as before, except now he or she will go on with the benefit of a high tech product and the happy support of his or her physician, mother and significant other. In other words, “ecomodernism” seems to me another version of “having one's cake and eating it too.”

…If I decide in the end to be an ally of your political movement, I will easily forgive the label you chose and the flag you selected. But I will be convinced only when I have obtained a detailed list of your friends and your enemies. And please don't tell me that you have no enemies, and that it is all about tracing the obvious and inevitable path of reason and progress—because I know who has drawn that path. It is a providential God, which is not my God…As usual, those who fight against apocalyptic talk and catastrophism are the ones who are so far beyond doomsday that they seriously believe that nothing will happen to them and that they may continue forever, just as before.”

Latour goes on to tell the audience in the symposium organized by Shellenberger and Nordhaus:

“I am doubtful that the only obstacle in the way of reaching the land of milk and honey is the resistance of environmentalists to embracing the ecomodernist cause.”

Shellenberger continues to use this discursive tactic of blaming, as Latour puts it, “the resistance of environmentalists to embracing the ecomodernist cause” as the source of all the world’s problems. But in describing the implications of Latour’s break with the institute in his 2015 farewell speech (where he expressed his view that the institute was ultimately a deeply misguided PR project built to frame environmentalists as the biggest enemy of future ‘progress’) Kallis and Bliss go on to argue that,

“…postenvironmentalism was indeed a communication project developed by two directors of PR firms. A cautious and complex story of humanity's entanglements within the web of life like Latour's could not be the frame for the simple messages Lakoff calls for. Like the conservative message makers before them, post-environmentalists wanted to communicate a straightforward vision; hence their story of post-war glory. But this narrative inevitably draws on conventional views of modernity that portray progress as a process of ever-greater control and separation between society and nature, reproducing a prevalent view of science as something pure and separate from ideology and politics.”

“Don’t think of an elephant” 🐘

The ‘anti-woke post-environmental’ frame6 advanced by Shellenberger and similar climate contrarians like Bjorn Lomborg appears to be an effective climate delay messaging campaign that took Lakoff’s theory of framing to heart, but just not in the progressive direction Lakoff intended. Perhaps most concerning is its ‘a-political’ framing of climate delay. As Kallis and Bliss point out, by framing their vision as “something pure and separate from ideology and politics,” everyone opposed to their vision automatically becomes ideologically compromised by ‘wokeism’ (or ‘climatism’ à la Hulm and Shellenberger). This strikes me as a deeply anti-democratic mode of political communication that leads people like U.S. presidential candidate Vivek Ramaswamy, for example, to claim that the main political divide in the U.S. isn’t between left or right, or democrats and republicans, but “between pro-Americans and anti-Americans.”

For George Lakoff, who often lambasted the political left in his writing for their failure to use framing effectively, one of the main lessons of environmental framing which he sought to capture in the title of his 2004 book “don’t think of an elephant” is to “Always go on offense, never defense. Never accept the right’s frames—don’t negate them, or repeat them, or structure your arguments to counter them. That just activates their frames in the brain and helps them” (2010, p. 79). But it’s also clear Lakoff adhered to a systemic view of framing. As he put it, the (progressive) environmental movement “need[s] a much better communications system. In addition to serious framing research institutes, such a system needs training facilities, a system of spokespeople in every electoral district, and bookers to get then booked in the media.”

Shellenberger, and the Breakthrough Institute clearly took this latter message of Lakoff’s to heart, creating an entire framing research institute devoted to advancing the ecomodernist message. But recognizing the systemic nature of communicative framing in shaping public action and policy on climate makes things much more complicated than just choosing the right words to frame an environmental message. With this in mind, Kallis and Bliss conclude their discourse analysis of the Breakthrough Institute’s messaging machine with a similar concern:

“Political ecologists in a Foucauldian tradition have shown how environmental battles are wars of truth, what comes to be seen as truth being partly an effect of power (e.g. Sletto 2008). One may interpret this like conservatives and the post-environmentalists did: a call to wield power in the service of one's preferred truth. Democracy is instead about limiting such power over truth. Latour's (2004) political ecological vision is one of democratizing the scientific institutions that produce truth claims, making their ideological stakes transparent. The question remains, however, how humble, plural approaches, open to their weaknesses, transparent about their values, and willing to engage in dialogue, can politically compete with moneyed communication machines that spread simple messages…”

For me, one of the key challenges ahead for environmental communicators will not only be to develop new communication tools and techniques informed by ecolinguistic and environmental communication research. But more challenging, we will likely need to develop new communication systems that restore and cultivate democratic principles for a multilingual, multimodal and multispecies public sphere: a planetary town hall that is capable of surviving our current anti-democratic digital age of post-truth platform capitalism theorized by scholars like Shoshana Zuboff, Nick Srnicek, and Bram Büscher. Luckily, I think there are many examples of such pro-democracy environmental communication systems taking shape across offline and online spaces around the world. One of the main tasks ahead for environmental communicators concerned about fostering a more democratic, just and sustainable world will simply be to identify and support these emerging communication systems as best we can.

📚 What I’m reading

A World in a Shell: Snail Stories for a Time of Extinctions. By Thom van Dooren. MIT Press. 2022.

“In this time of extinctions, the humble snail rarely gets a mention. And yet snails are disappearing faster than any other species. In A World in a Shell, Thom van Dooren offers a collection of snail stories from Hawai’i—once home to more than 750 species of land snails, almost two-thirds of which are now gone. Following snail trails through forests, laboratories, museums, and even a military training facility, and meeting with scientists and Native Hawaiians, van Dooren explores ongoing processes of ecological and cultural loss as they are woven through with possibilities for hope, care, mourning, and resilience.”

🎧 What I’m listening to

The Surfer’s Journal Soundings Podcast. Interviews with Gerry Lopez and Selema Masekela. I really enjoyed listening to these two interviews, and they both provide interesting perspectives on human relationships with the ocean, and the natural world more broadly, made possible through a particular ‘mediational tool,’ the surfboard.

“I really believe surfing is something that is not easy to continue doing, that for whatever reasons, you lose interest, you get out of shape, you let it go just a little too long, that passion, or desire just kind of fades away. I’ve had a lot of friends who have just kind of…gave up. And I could never really understand because surfing always brought me such joy, and a sense of completeness, that if I’m surfing, I’m alive, and as long as I keep surfing, I’ll stay alive. One of the things that’s been interesting to me, that for a long time I’ve practiced yoga in my life, I thought they were pretty similar, even parallel paths. And as time has gone on, I mean shoot, I’ve been surfing since I was 10 years old, this year will be 65 years, I think I’ve come to see that maybe yoga and surfing are the same path. And maybe the Hawaiians were really on to something a long time ago.

Also listening to: Outside/In: When Protest is a Crime

“When members of the Oceti Sakowin gathered near the Standing Rock Reservation to protest the Dakota Access Pipeline, they decided on a strategy of nonviolent direct action. No violence… against people. But sabotage of property – well, that’s another question entirely. Since the gathering at Standing Rock, anti-protest legislation backed by the fossil fuel industry has swept across the country. What happened? When is environmental protest considered acceptable… and when is it seen as a threat?This is the first of two episodes exploring the changing landscape of environmental protest in the United States, from Standing Rock to Cop City and beyond.”

“So much about Hawaiian land protection and water protection is about restoration of aina, restoration of the land. And that includes water restoration, letting water remember where it should go, letting water flow where it needs to go because it was already a system that protected us”

The Wolf Connection Podcast: An interview with Michelle Lute - Wildlife For All: “Michelle Lute is the Co-Executive Director for Wildlife For All, whose mission is to reform wildlife management in the U.S. to be more democratic, compassionate and focused on protecting wild species and ecosystems.”

👀What I’m watching

Madre Mar, by Patagonia Films.

“The local people have worked the waters of the Sado Estuary Natural Reserve in Portugal for hundreds of years, coexisting with the dolphins, fish and shellfish, supported by the region’s rich seagrass meadows. The practice of bottom trawling, which bulldozes the ocean floor, has wiped out nearly one-third of the world's seagrass meadows. Raquel Gaspar, marine biologist, mother and cofounder of the Portuguese NGO Ocean Alive, is on a journey to protect and re-meadow Sado’s seagrass habitat. In Patagonia Films’ Madre Mar, Raquel partners with a group of local fisherwomen to restore this crucial piece of the ocean’s ecosystem–one that provides habitats for sea life and 10 percent of the carbon captured in the ocean.”

🔍 Tools & Resources I’m exploring

Prefigurative Politics in Practice, from the Commons Social Change Library.

“If we don’t take a bit of time to dream about better futures, if we keep reacting to whatever the current trends are or the next over-the-horizon trends, than we will just keep stumbling in the darkness towards a cliff. So, the first thing we need to do is dream about where we need to go, and then put that light on that hill, and walk towards that light, because then across every sector, we can then have convergent effort towards something better that we actually create. (Pia Andrews, 2022)”

Citational politics training module, by the CLEAR Lab: “An introductory assignment on the politics of citation, with a guided quiz for students to think about how they might change their citation practices to best align with their values.”

How board games can get people involved in climate action, by Sam Illingworth, in the Conversation. Aug 1, 2023

📰 News and Events

Why was there no water to fight the fire in Maui? By Naomi Klein and Kapuaʻala Sproat, in the Guardian. Aug 17, 2023

“Hawaii is indeed in an emergency, but it needs emergency proclamations that operationalize aloha ʻāina, not ones that push it aside by opportunistically suspending inalienable water laws and dismissing diligent public servants.…Right now, the eyes of the world are on Maui, but many don’t know where to look. Yes, look to the wreckage, the grieving families, the traumatized children, the incinerated artifacts, and donate what you can to community-led groups on the ground. But look below and beyond that too. To the aquifers and streams, and the plantation-era diversion ditches and reservoirs. Because that’s where the water is, and whoever controls the water controls the future of Maui.”

Montana’s landmark climate ruling: three key takeaways: “A judge last week ruled the young plaintiffs have the right to a clean environment – and experts say this changed the climate litigation landscape.”

How a surfing sea otter revealed the dark side of human nature. By Patricia MacCormack in the Conversation

Can upcoming referendum in Ecuador stop oil drilling in Yasuní National Park? By Kimberley Brown in Mongabay. August 11, 2023

Yes it can! Ecuador votes to halt oil drilling in Amazonian biodiversity hotspot: Referendum result comes as blow to president, requiring state oil firm to dismantle operations area of Yasuní. Associated Press, in The Guardian. August 21, 2023

Climate Education Suffers From Partisan Culture Wars: But teachers in many states are stepping up to the challenge and providing students with knowledge and tools for resilience. By Eduardo Garcia, in the Revelator.

📚 Research

Environmental users abandoned Twitter after Musk takeover by Charlotte H. Chang, Nikhil R. Deshmukh, Paul R. Armsworth, Yuta J. Masuda in Trends in Ecology and Evolution. (2023).

Environmentalism of the Rich. By Peter Dauvergne. MIT Press. (2016).

How to Do Critical Discourse Analysis: A Multimodal Introduction. Second Edition. By David Machin and Andrea Mayr (2023)

Nestwork: New Material Rhetorics for Precarious Species. By Jennifer Clary-Lemon. Penn State University Press: “In this innovative ethnographic study, rhetorician Jennifer Clary-Lemon examines human-nonhuman animal interactions, identifying forms of communication between species and within their material world.”

The Toxic Ship: The Voyage of the Khian Sea and the Global Waste Trade. By Simone M. Müller, University of Washington Press. (2023).

Empirical Ecocriticism: Environmental Narratives for Social Change. Edited by Matthew Schneider-Mayerson, Alexa Weik von Mossner, W. P. Malecki, and Frank Hakemulder. University of Minnesota Press, 2023 (read the introduction):

“Most environmentally engaged scholars, thinkers, and activists agree that to respond to the existential challenges we currently face, we need new narratives about who we are, how we’re entangled with the rest of the natural world, and how we might think, feel, and act to preserve a stable biosphere and a livable future with as much justice as possible. But what kinds of stories should we tell? To which audiences? Through what media? Are some stories more impactful than others? Are some counterproductive? And how can scholars of literature, theater, art, digital media, film, television, and other cultural forms contribute to, expedite, or shape the historic socioecological transformation that is now underway?”

💡 Ideas

Storm Antoni: why naming storms is a risky business. By Jane Pilcher and

Anna-Maria Balbach in The Conversation:

“The naming of storms, streets or buildings is a complicated and risky business precisely because names are not just benign words. They are powerful cultural workhorses, brimful of meanings that say so much about who we are and how we experience the world.”

Heat Is Not a Metaphor: As the hottest summer on record draws to a close, how do we make sense of the images of a climate in crisis? By Alexis Pauline Gumbs in Harper’s Bazaar.

The Real Free Speech Threat: “Almost half the US states have criminalized protest in the past 5 years. They're not alone. The UK, Australia, Canada, France, Uganda, Mozambique, Brazil, Vietnam -- governments around the world are criminalizing climate protest in particular. That's the real free speech threat” — climate journalist Amy Westervelt.

Why climate despair is a luxury: Those facing flood and fire can’t afford to lose hope. Neither should we. By Rebecca Solnit In the New Statesman. (July 17 2023): “When you take on hope, you take on its opposites and opponents: despair, defeatism, cynicism and pessimism. And, I would argue, optimism. What all these enemies of hope have in common is confidence about what is going to happen, a false certainty that excuses inaction.”

Negative capability: When it comes to our complicated, undecipherable feelings, art prompts a self-understanding far beyond the wellness industry. By Cameron Allan McKean in Aeon Magazine.

Animals in the Room: Why We Can and Should Listen to Other Species. by Melanie Challenger in Emergence Magazine.

“It is often said that animals are, in some sense, silent. They grunt, yes. Or call. Or cry. Some of them sing. Some hiss. But they have no voices. They do not speak. They are silent because they lack both language and the minds that structure and generate meaning. Even those who argue for compassion towards nonhuman beings have historically perpetuated this idea. Consider one of the landmark publications in the animal advocacy movement. Our Dumb Animals was the title of the magazine published by the Massachusetts Society for Prevention of Cruelty to Animals from 1868 through to 1970. As the motto went, ‘We speak for those who cannot speak for themselves.’”

🗃️ From the Archive

“The most influential messages of the twenty-first century will be sent not through words and images but through heat and cold.”

- Nicole Starosielski, in Media Hot and Cold.

💬 Quotes I’m thinking about

I was sorry to hear of Jon Henner’s passing this month. I enjoyed and learned so much attending Jon's talk on Deaf Education and Sign Language at the American Association of Applied Linguistics in Portland, Oregon in March this year. His work on Deaf Education and Sign Language involved the development of the theoretical framework of Crip Linguistics, a framework which advances “a bigger and more flexible understanding of what language is.” As Jon put it,

“How you language is beautiful. Don’t let anyone tell you your languaging is wrong. Your languaging is the story of your life.”

—Jon Henner

“What is this dynamic alliance between an animal and the animate orb that gives it breath? What seasonal tensions and relaxations in the atmosphere, what subtle torsions in the geosphere, help to draw half a million cranes so precisely across the continent? What rolling sequence or succession of blossomings helps summon these millions of butterflies across the belly of the land? What alterations in the olfactory medium, what bursts of solar exuberance through the magnetosphere, what attractions and repulsions . . . ? For surely, really and truly, these migratory creatures are not taking readings from technical instruments nor mathematically calculating angles; they are riding waves of sensation, responding attentively to allurements and gestures in the topographical manifold, reverberating subtle expressions that reach them from afar. These beings are dancing not with themselves but with the animate rondure of the Earth, their wider Flesh.”

— David Abram, in Creaturely Migrations on a Breathing Planet, Emergence Magazine.

Thanks so much as always for your interest in my work, and if you found this digest useful, please consider sharing with others who might find it interesting too😊 I'd also love to hear from you. Leave a comment to let me know what you think about this digest, what areas of environmental communication you’re involved in/most interest you, or anything you’d like to see more of in Wild Ones:)

If you found this newsletter useful in your own life and work, consider subscribing to receive future Wild Ones posts in your inbox. Wild Ones will always be a free educational resource, but if you find value in this newsletter and would like to support my research and writing to keep it going, consider going for a paid subscription option too:)

‘Indexical alignment’ is a concept in linguistic anthropology that, in a nutshell, captures how the language we use indexes or ‘points’ to our identity in someway, like smoke points to the presence of fire. In more traditional in linguistics, ‘indexical signs’ (also called ‘deictic terms’) are words that ‘point’ to the physical context one is in: so ‘I,’ ‘you,’ ‘this,’ and ‘that’ or ‘here’ and there’ are also indexical signs or pointers. And because they shift in meaning depending on the point of view of the speaker, they are also sometimes called ‘shifters.’ Linguistic anthropologists, however, are more interested in the wider social and cultural context that indexical signs help speakers point to, such as how certain styles of speaking or embodied movement give speakers a handy resource to index or ‘point to’ an identity associated with, for example, social class, sexuality, race, or gender (masculine or feminine) identities. Or, in the case of ‘wokeness’ that I explore in this post, the alignment of one’s identity with anti-racist politics (see, for example, Elinor Och’s famous ‘indexing gender’ paper, or Scott Kiesling’s ‘dude’ paper).

One of the examples Olúfẹ́mi O. Táíwò gives for the first strategy is an internal REI podcast from 2022 where the company’s ‘Chief Diversity and Social Impact Officer’ uses “progressive language to union bust,” as Táíwò puts it. Here is an excerpt from that podcast:

“Hi REI. My name is Wilma Wallace and I serve as your Chief Diversity and Social Impact Officer. I use she/her pronouns and am speaking to you today from the traditional lands of the Ohlone people…one of the top questions that must be on people's minds is why REI doesn't think unionization is the right thing for the co-op or for the employees.”

In a research article in the Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, “Brands Taking a Stand: Authentic Brand Activism or Woke Washing?” by Jessica Vredenburg, Sommer Kapitan, Amanda Spry, Joya A. Kemper, the authors define wokewashing like this: “Specifically, woke washing is defined as “brands [that] have unclear or indeterminate records of social cause practices” (Vredenburg et al. 2018) but yet are attempting “to market themselves as being concerned with issues of inequality and social injustice” (Sobande 2019, p. 18), highlighting inconsistencies between messaging and practice (Vredenburg et al. 2018).”

Bjorn Lomborg also uses similar delayist language, saying climate change is real while at the same time writing books with titles like False Alarm: How Climate Change Panic Costs Us Trillions. Greta Thunberg, the biggest climate alarmist of all for Lomborg, has been naively coopted by the ‘radical woke left.’ Lomborg asserts the same basic argument as Hulme, which is to claim that any kind of climate policy initiative comes at the expense of social welfare efforts to relieve poverty and hunger. In a nutshell, he seems to be saying that he is the real climate justice warrior because the policies climate activists want to encat will hurt poor and marginalized communities.

The details of his article grossly misrepresent water rights conflicts in West Maui. Shellenberger, in effect, blames Native Hawaiians for ‘woke dogmatism’ as he claims they delayed firefighters from using water in the West Maui Land’s reservoir reserved for Native Hawaiian farms, water which if used would have prevented the fires from spreading in Lahaiana he claims. This is false. According to the local news station KITV4: “The fire department confirmed air crews were grounded because of the high winds. So they could not have flown mauka [mountain side] to scoop water from West Maui Land’s reservoir. KITV4 was also told that supply does not feed into the county’s water system, so firefighters would not have access to it through hydrants.” Native Hawaiian community members in Lahaiana also addressed this frustrating misrepresentation of Maui water issues in a press conference. Shellenberger’s anti-woke narrative, furthermore, leads him to omit in his discussion how the plantation-era company West Maui Land Co. has been responsible for desiccating Lahaina for decades, diverting water from the local community to feed tourist resorts and golf courses while trampling over Native Hawaiian water rights in the process. In this way, Shellenberger’s anti-woke discourse directly serves the project of plantation disaster capitalism in Lahaina supporting companies like West Maui Land Co. in their effort to benefit from climate change as a disaster threat-multiplier in Hawai‘i at the expense of local communities.

One of the ways Lakoff defined ‘frames’ and ‘framing’ in his famous article on environmental framing is as follows: “Words are defined relative to frames, and hearing a word can activate its frame* and the frames in its system* in the brain of a hearer. Words themselves are not frames. But under the right conditions, words can be chosen to activate desired frames. This is what effective communicators do. In order to communicate a complex fact or a complex truth, one must choose one’s words carefully to activate the right frames so that the truth can be understood” (p. 73).