🌿Wild Ones #61: Environmental Communication Digest

Wolf conservation: ‘The mythical wolf’ and ‘the real wolf’ + The language of “sacrifice” + What is Public Engagement? + more!

Hi everyone, welcome back to Wild Ones, a weekly newsletter by me, Gavin Lamb, about news, ideas, research, and tips in environmental communication. If you’re new, welcome! You can read more about why I started Wild Ones here. Sign up here to get these digests in your inbox:

📚🐺 What I’m reading

In this edition of Wild Ones, I look at some of the political controversy surrounding the reintroduction of gray wolves in the U.S. I focus on wolves here, but I think public discourse around wolves sheds light on the broader political challenges environmental communicators face in a time of increasing polarization. Thanks for reading!

On February 10, a U.S. federal judge restored protections for gray wolves in much of the United States after gray wolves had lost protections under a Trump policy to delist them from the Endangered Species Act.

One caveat: Wolves in Montana, Idaho, and Wyoming aren’t included because they were delisted in those states by Congress in 2011. For example, it’s still completely legal to aerial hunt wolves from planes in Montana, and the governor of Idaho recently signed a bill to kill 90% of wolves in the state.

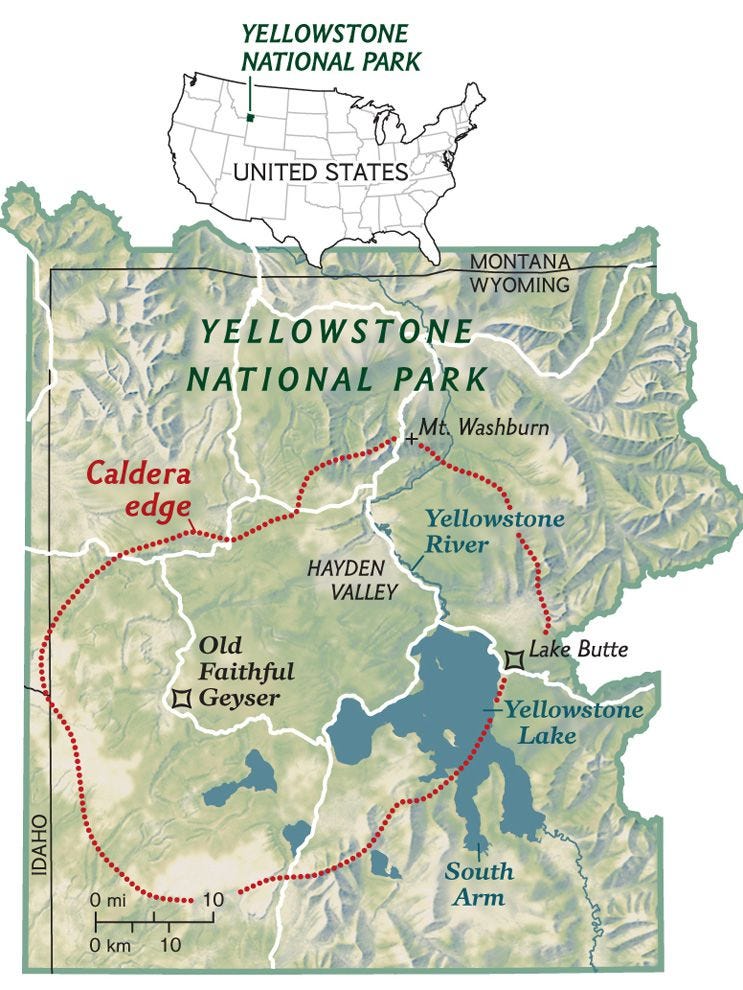

Journalist Joshua Partlow reported on the story in a February 2022 piece in The Washington Post, writing that “The controversy over wolf hunting this year has been particularly intense in Montana and the area around Yellowstone National Park, where gray wolves were reintroduced in 1995 after being eliminated by hunters in the 1920s.”

“Wolves are likely to remain a political football in the larger predator political arena for quite some time to come” reported journalist Kylie Mohr in High Country News:

“The shifting status of wolves is set against a backdrop of wildly varying attitudes toward apex predators. Many hunters and ranchers believe protections are not only no longer warranted, they also contribute to wolf attacks on livestock and big game, while conservationists note that wolves still don’t occupy anywhere close to their historical range. A 2020 ballot initiative to reintroduce the species in Colorado split down geographic lines on a slim margin, with urban voters mostly in favor and rural voters opposed.”

A couple of years ago I read a fascinating book called American Wolf by journalist Nate Blakeslee. The book explores the controversy around wolf reintroduction efforts in Yellowstone National Park through interviews with hunters, ranchers, conservationists, local community members, and wolf enthusiasts visiting the park. The main protagonist in the book is ‘06,’ a charismatic alpha female wolf who was named after the year she was born. He traces the story of 06’s life primarily through the lens of Rick McIntyre, a park ranger with the Yellowstone National Park Service who has spent much of his life working to restore wolf packs to the park. Here’s an informative clip of Nate Blakeslee explaining his motivation behind writing the book American Wolf during his interview with PBS:

In the book, Blakeslee weaves together science, politics, and personal narrative in a way that reads like a gripping thriller, and after reading the book, I got the audiobook to relisten and the narrator does a great job bringing the drama of the book to life! But the events Blakeslee documents in the book are tragic – the wolf 06 was eventually killed in 2012 by a hunter when she roamed outside the protected boundaries of Yellowstone National Park. But American Wolf is also a hopeful story, as Blakeslee highlights the tireless work of wolf advocates like Rick McIntyre, the other main protagonist in the book. Rick is a park ranger who has spent most of his career with Yellowstone’s Interpretation Division, the educational outreach arm of the park aimed at educating visitors about wolves and other wildlife in the park. Blakeslee writes that:

“Rick’s dream, though he seldom described it as such, was to someday tell a story so good that the people who heard it simply wouldn’t want to kill wolves anymore.”

I highlighted this quote in the book because it struck me as powerful at the time, but thinking about it now, it raises an important question for environmental communicators: how can ‘good storytelling’ transform human relationships with the “more-than-human”1 world for the better?

For Rick, one key strategy was to shine a light on the fascinating lives of individual wolves making a home in the park as they hunted elk, formed close bonds with other wolves, and roamed their territory. Getting people to see the world from a wolf’s-eye-view was an important communication strategy for Rick to get his audience not just to care about wolves during their brief visits to the park, but to spark more enduring emotional connections that might translate into the political will to protect wolves over the long term.

“We can be ethical only in relation to something we can see, feel, understand, love, or otherwise have faith in.”2 – Aldo Leopold

‘Making Room for Cattle’

At least two competing ‘wolf discourses’ (each with particular frames, narratives, rhetorical devices, and metaphors for talking about wolves) seem to emerge in Blakeslee’s reporting: ‘wolves as threats,’ a view mainly voiced by hunting and ranching interest groups, and ‘wolves as an ecologically stabilizing force,’ a view voiced by conservationists.3

Wolves as threats: In a fact-checking piece on a wolf eradication bill signed into law in Idaho in May 2021, Outside journalist Wes Siler’s sheds light on some of these conflicting narratives. Siler quotes the executive vice president of the Idaho Cattle Association, who says plainly that the ‘wolf problem’ is that wolves are a direct threat to ranchers’ economic interests:

“A cow taken by a wolf is similar to a thief stealing an item from a production line in a factory.” Wisconsin cattle farmer Eric Koen echoes this view, telling Grist in 2021 when the state saw one of its most lethal wolf hunts in decades with hunters killing 218 wolves in just 3 days: “The bigger the [wolf] population, the more problems that we’re having on the farm…It isn’t only the killing and injuring of animals, they put tremendous stress on our herds.”

Wolves as an ecologically stabilizing force: On the other hand, Indigenous tribes, conservationists, and environmental advocacy groups have argued against the narrative that wolves are a threat, contesting claims made by hunting and ranching interest groups that killing most wolves is just “common-sense predator management.”

For example, a recent study examines Ojibwe perspectives toward wolf stewardship in the aftermath of Wisconsin’s disastrous February 2021 wolf hunting season (in which more than 20% of the wolf population in the state was killed in less than three days). The authors write that “the Ojibwe contend that this gross overharvest is not only culturally abhorrent but threatens resources the tribes depend upon.” This is not a new phenomenon but reflects a history of colonization in which “both wolves and Indigenous peoples” were responded to as threats by white settlers. As the authors of the study write, “[b]oth the wolf and the Native peoples were despised and persecuted by many in the newly forming colonies.”

Wolf conservation biologists have shown that wolves create an ecologically beneficial ‘trophic cascade.’ In other words, as wolf populations begin to increase, they trigger a kind of ripple effect through the food chain, predating abundant elk populations by over fifty percent, which gives beavers, bison, new-growth aspen, and willow forests room to flourish.

This isn’t only because wolves predate more elk. Some conservation biologists have argued that wolf-created trophic cascades are due, at least in part, to the ‘ecology of fear’ wolves create through the predation risk their presence on the landscape signifies to elk. In turn, elk’s fear of wolves lead them to avoid certain areas, allowing space for other species to flourish, like beavers, foxes, eagles, and willow:

So if wolves’ presence in the landscape is ecologically beneficial in part due to their creating an ‘ecology of fear’ as apex predators, I can understand how wolves’ presence in the landscape stresses cattle inhabiting the same landscape, as rancher interest groups claim. More than just fear though, some anti-wolf government officials have described the number of cows killed by wolves as a ‘disaster.’ However, according to a fact-checking piece by Outside magazine on Idaho wolf kills, they report:

“In 2018 there were 113 confirmed wolf kills of cows and sheep. In 2019 that number was 156, and in 2020 it was 84. That gives us a three-year average of 113 wolf kills per year in the state. There are currently 2.73 million head of cows and sheep in Idaho. That means confirmed wolf-caused losses amount to 0.00428 percent of the state’s livestock.”

So, I struggle to see how wolf livestock depredation coming in at around 0.00428 percent can be called a ‘disaster’ for the cattle industry in Idaho.4 If we let the facts speak for themselves, it appears the cattle industry has been a much more horrendous disaster for wolves. Not to mention a disaster for the earth, as “cattle are the No. 1 agricultural source of greenhouse gases worldwide.’’ As Montana-based wolf conservationist Mike Phillips argues:

“It was the cattlemen that developed a pathological hatred of the gray wolf to make room for European cattle. The grizzly bear was pushed to the brink of extinction in the United States to make room for cattle. Even to this day, predators continue to be persecuted to make room for cattle.”

It’s in this context – to ‘make room for cattle,’ not wolves – that we should understand how gray wolves have become ‘a political football’ in the U.S.

Specifically, wolf reintroduction and conservation efforts are portrayed by conservative state governments as an activist cause advanced by left-wing conservationists and environmental organizations.

For example, take this statement from Luke Hilgemann, president and CEO of Hunter Nation, whose Kansas-based hunting interest group was behind the successful lawsuit allowing that disastrous 2021 Wisconsin hunt (when hunters using dogs killed over 200 wolves in three days) to proceed. When wolves were relisted under the Endangered Species Act (ESA) in February this year, overturning a Trump-era ruling to delist wolves from the ESA and return wolf management to the states, Hilgemann said:

“We are disappointed that an activist judge from California decided to tell farmers, ranchers, and anyone who supports a balanced ecosystem with common-sense predator management that he knows better than them.”

This right-wing politicization of wolf protection laws echoes similar views expressed by farmers and hunters protesting wolf reintroduction campaigns in Europe too. For example, the authors of a recent study examining how public attitudes towards wolves are connected to political attitudes in Europe write:

“In some parts of Europe…[f]armers (and hunters) feel cast aside by society, relabeled as villains, whereas the wolves are “symbolic heralds of a newly invigorated naturality” (Buller, 2008:p. 1587). This conflict in ideologies has seen (illegal) killing of wolves become a symbol of protest, an act of resistance against governments that are perceived to have excluded the rural public from the broader public agenda and shifted favor toward middle class environmentalist interests”

“This study,” the authors go on to argue, “suggests that political affiliation is more important than other demographic factors (such as proximity to wolves) in predicting support or opposition to wolf conservation…”

While people’s position as pro- or anti-wolf might seem to align with how left or right they fall on the political spectrum, some wolf biologists argue that the politicization of public discourse about a ‘wolf problem’ in the U.S. is fueled by influential livestock and hunting interests groups (like Hunter Nation in the U.S). It even appears that most people in the U.S. who are affiliated with political parties on the right, when surveyed, do not actually hold views advanced by ranching and hunting interest groups (on a side note: poll after poll show right-wing interest groups and their captured politicians to be out of step with voters). It just seems this way because the lobbying efforts of these interest groups have had such a massive influence on the politicians responsible for anti-wolf policies in recent years. For example, John Vucetich, a wolf expert and Professor of Biology at Michigan Technological University, argues:

“If you look at sociological data, wolves are not controversial. The Endangered Species Act is also not at all controversial. Even people who self-identify as Republicans or politically conservative have really strong, positive views about the Act. The controversy does not come from constituents. It comes from special interest groups leaning hard on members of Congress.”

‘The Science of Intolerance’

The map below show the historic range for gray wolves in the U.S. with most wolf packs in the U.S. confined to ‘the greater Yellowstone ecosystem.’

Wolves were increasingly hunted across their historic range in North America from the Arctic Circle to present-day Mexico City up until the 1920s when they were trapped and poisoned in government-sponsored hunts to the brink of extinction. In Yellowstone National Park, the last two wolves born in the park– both just pups — were shot in 1926 by Yellowstone park rangers.

In 1974, wolves were listed under the U.S. Endangered Species Act, and in 1995, wolves were reintroduced in Yellowstone national park and surrounding states. Since then, a long-running study monitoring wolves in the region has shown the remarkably beneficial impact apex predators like wolves have on the ecosystems they inhabit.

However, despite these findings contributing to the ‘best available science’ meant to shape conservation policy and enforcement of wolf protection laws, there seems to be an overwhelming pressure on state and federal agencies tasked with enforcing wolf protections under the Endangered Species Act to define the ‘wolf problem’ through the lens of the cattle industry’s economic interests.

For example, a 2013 ‘Policy Perspective’ article entitled “Removing Protections for Wolves and the Future of the U.S. Endangered Species Act (1973)” examines a proposed rule in that year by the U.S. Fish & Wildlife (USFW, the federal agency tasked with enforcing wolf protections in the United States). The policy review shows that USFW ignored a significant body of scientific knowledge by “assert[ing] that areas where wolves once existed but no longer exist are “unsuitable habitat” because people in these areas lack tolerance for wolves.”

The authors refer to this new re-interpretation of the Endangered Species Act as relying not on the standard of ‘best available science,’ but on ‘the science of intolerance.’ Intolerance is defined as an attitude that motivates people, due to their economic interests connected to landscapes, to resist wildlife restoration.

As the logic of the science of intolerance goes, ‘suitable areas’ for wolves are those places where “conflict with humans and their livestock is low…” So, this means that “The areas considered ‘unsuitable’ [for wolves] are not occupied by wolves due to human and livestock presence and the associated lack of tolerance of wolves.” The authors of the article go on to write:

“A central tenet of the proposed [2013] delisting rule is: ‘the primary determinant of the long-term conservation of gray wolves will likely be human attitudes toward this predator.’ Although bound by the ESA to base its listing and delisting decisions on the best available science, the [US Fish and Wildlife] does not refer to any of the scientific literature on human attitudes toward wolves to justify its determination. This failure is egregious because much is known about this topic.”

‘Throughout a significant portion of its range’

As the Endangered Species Act phrases it, an endangered species is one that is “in danger of extinction throughout all or a significant portion of its range.” The phrase ‘a significant portion of its range’ is key here, as the authors of the 2013 ‘policy perspective’ article point out: the U.S. Fish and Wildlife agency was essentially arguing at the time to redefine the ‘range’ of wolves as their ‘current range.’ In other words, even if wolves’ ‘current range’ increasingly dwindles to a few small strips of land labeled as ‘wildlife refuges,’ we can never reverse this dwindling habitat because we can’t stop people who live in places wolves used to live, and who dislike wolves, from killing wolves. Wolf biologist John Vucetich puts it like this:

“Go back to that legal definition — that language, “throughout all or a significant portion of its range” [in the Endangered Species Act]. It’s the basis for asking the question: How much damage is too much? In the Lower 48, wolves currently occupy about 15 percent of their historic range. It’s really hard to imagine that you could lose 85 percent of the species’ range and say, “That’s no big deal.”

The 2013 wolf delisting proposal didn’t succeed at the time, although it invoked a clever representational rhetoric of wolf intolerance, underpinned by the rationale that it is hopeless trying to save wolves outside their “current range” because, as the authors put it: “some people dislike wolves.” But the framing behind it was a striking example of how the discourse of wolf ‘threat’ and ‘risk’ promoted by the livestock industry can easily gain influence and potentially end up being written in to mainstream conservation policy.

Whether or not these laws are ultimately adopted, they powerfully influence how state governments in the U.S. talk about (and often oppose) wolf conservation efforts. This is in no small part due to the immense amount of money these industries invest in building incredibly effective political communication networks that work in their favor, effectively trumping ‘the best available science.’ Instead of conservation science, another simple logic gains primacy: where there are cattle, there can never be wolves.

This ‘representational rhetoric of intolerance’ advanced by cattle ranching interest groups echoes another policy from more than a hundred years earlier. As historian Nick Estes writes in his book, Our History is the Future:

“The extermination of the buffalo was incredibly effective and efficient. In two decades, soldiers and hunters had eradicated the remaining 10 to 15 million buffalo, leaving only several hundred survivors. The “Indian problem” was also a “buffalo problem,” and both faced similar extermination processes, as much connected in death as they were in life. The destruction of one required the destruction of the other. The treaty clause “so long as the buffalo may range” was effectively a warrant to kill millions of buffalo, which translated literally into the killing of Indians and the seizure of millions of acres of 1868 Treaty territory—a direct attack on Indigenous sovereignty.”

The inclusion of the clause “so long as the buffalo may range” in The 1868 Fort Laramie Treaty, as Estes shows, smuggled in a policy of ‘managed extinction’ for both bufallo and people. It shows how the power to define ‘the range’ of wildlife, as their ‘current range’ is whittled down year by year, is connected to a similar history of colonial disposessession and violence towards human and nonhuman beings, making room instead for another human-nonhuman relationship: white guys and their European cattle.

At least, that’s how Mike Phillips puts it, a long time wolf conservationist working for the U.S. Fishand Wildlife Service and National Park Service, and later, a senator for the Montana state legislature until 2021. In a fascinating interview on the excellent For the Wild podcast, Phillips describes how replacing bison with European cattle was central to wolf eradication efforts in the U.S.:

“we've already spoken about the destruction of the plains bison that was very much justified on the grounds that the grasslands needed to provide forage for European cattle. We spoke about the destruction of the gray wolf. It was the cattlemen that developed a pathological hatred of the gray wolf to make room for European cattle. The grizzly bear was pushed to the brink of extinction in the United States to make room for cattle. Even to this day, predators continue to be persecuted to make room for cattle.”

‘The mythical wolf’ and ‘the real wolf’

In the interview, Mike Phillips further suggest that one of the biggest challenges to wolf conservation has been a ‘war on the gray wolf’ motivated by a notion of ‘the mythical wolf.’ “Gray wolves are actually really easy to coexist with,” Phillips says. Yet the challenge lies in a widespread discourse of wolves, framing them as “hav[ing] an almost supernatural ability to exercise their predatory will on a whim. And by doing so they create a wake of death and desolation and destruction everywhere they go. Nothing could be further from the truth. For the gray wolf life is a daily struggle to survive.”

Taken together, the economic drive ‘to replace bison with European cattle’ coupled with an anti-wolf narrative of ‘the mythical gray wolf’ have fueled a common project: the eradication of wolves in the U.S to make room for cattle and a small group of human benefactors.

Here’s a list of some of the news reports, research articles and books I used for this post. Please share any others you recommend in the comments:)

Timeline of wolf conservation and controversy in the U.S. By EarthJustice.

How gray wolves divided America: Many people love wolves. How did saving them become so controversial? By Benji Jones in Vox. Feb 12, 2022

Federal judge restores protections for gray wolves in much of U.S., reversing Trump policy. By Joshua Partlow, in the Washington Post. February 10, 2022

5 things to know about gray wolves regaining Endangered Species Act protection. By Kylie Mohr in High Country News. Feb. 15, 2022

Who’s Afraid of the Big Bad Wolf Scientist?: Rob Wielgus was one of America’s pre-eminent experts on large carnivores. Then he ran afoul of the enemies of the wolf. By Christopher Solomon in the NYTimes (2018).

Why have gray wolves failed to gain a foothold in Colorado? By Paige Blankenbuehler in High Country News (2021). “It’s not the wolves themselves, but what they represent to people that really, really matters.”

Attitudes Toward Wolves in the United States and Canada: A Content Analysis of the Print News Media, 1999–2008. By Houston, Bruskotter, Fan, (2010) in Human Dimensions of Wildlife.

Bordering Ecosystems: The Rhetorical Function of Characterization in Gray Wolf Management. By Aaron T. Phillips in Environmental Communication (2017).

From Obstructionism to Communication: Local, National and Transnational Dimensions of Contestations on the Swedish Wolf Cull Controversy. By Erica von Essen and Michael Allen in Environmental Communication (2017).

American Wolf: A True Story of Survival and Obsession in the West. By Nate Blakeslee (2018).

Rocky Mountain Wolf Project: “The Rocky Mountain Wolf Project aims to improve public understanding of gray wolf behavior, ecology, and options for re-establishing the species in Colorado.”

Finally, I’ve tried to follow public discourse about gray wolf reintroduction and conservation efforts, mostly in the United States but also in Europe too. This also led me to consider the political controversies surrounding efforts to reintroduce other apex predators (grizzly bears, jaguars, and lions) around the world. The CONVIVA project is doing interesting work on this.

🎧 What I’m listening to

“You know, we can put an astronaut on the moon and bring her home, we can take your heart out of your chest and put it back better than before. I promise you we can coexist with the gray wolf but the livestock industry stands in sharp opposition. So we continue to bow down to the great hamburger.”

📰 News and Events

The Supreme Court has curtailed EPA’s power to regulate carbon pollution – and sent a warning to other regulators. By Patrick Parenteau in The Conversation.

“(Re)thinking Landscape Conference” (Yale Environmental Humanities) (September 29, 2022).

UEA/Willowherb Speculative Nature Writing Call for Essay Proposals: Submissions open 15 June–15 July.

Spain gets the world’s first heat wave naming system. By Kate Yoder in Grist.

📚 Research

Ecocritical Readings of Academy Award-Winning Animated Shorts, by Virág Vécsey in Environmental Communication: “…this article is a textual analysis from an ecocritical viewpoint on Academy Award-winning animated short films (1939–2019). It examines how these films have represented the relationship between human and nature over the past 90 years. The aim of this paper is to contribute to our understanding of changes in people’s attitudes towards nature as represented in popular culture.”

Language and Social Justice in US Climate Movements: Barriers and Ways Forward. By Julia Coombs Fine in Frontiers in Communication.

Ecolinguistics for and beyond the Sustainable Development Goals. By Meng Huat Chau, Chenghao Zhu, George M. Jacobs, Nimrod Lawson Delante, Alfian Asmi, Serena Ng, Sharon Santhia John, Qingli Guo and Krishnavanie Shunmugam, in theJournal of World Languages.

What is Public Engagement and How Does it Help to Address Climate Change? A Review of Climate Communication Research. By Ville Kumpu in Environmental Communication: “Public engagement, communication, and societal change are approached predominantly from a psychological perspective that emphasizes personal engagement with climate change…Communication is predominantly approached as a pragmatic tool that can be used to address climate change rather than an object of theorization.”

💡 Ideas

The Way We Talk About Climate Change Is Wrong: The language of “sacrifice” reveals we’re stuck in a colonial mindset. By Priya Satia, in Foreign Policy:

“…the language of sacrifice for the future is uncomfortably close to the mindset that landed us at this precipice. It was precisely by training their eyes on the future, with the help of the concept of time discounting and theories of how to overcome it that germinated in the era of European colonialism, that previous generations became profligate with the Earth’s resources—which should give us pause in reprising the language of sacrifice today…It is time, in short, to stop sacrificing our humanity. Consuming less is no sacrifice in this perspective, but a profoundly self-loving act. Human civilization as we know it should expire. History has been a nightmare from which we all must awake.”

“Handshake Activism” Won’t Defuse the Climate Emergency. We need to mobilize many more people from all walks of life, say climate activists Kumi Naidoo and Luisa Neubauer. By Bill McKibben in The Nation.

Cascade Learning for Environmental Justice. By Prerna Srigyan in EnviroSociety.

Interesting thread on the keyword “nature-based solutions” ⬇️

(Wolf) Quotes I’m thinking about

“My greatest understanding of humans is through and about wolves. Some people love them and some people hate them, and my greatest interest is to understand why we are the way we are. But I’ve learned that no matter what side you’re on, we have a deep inability to explain ourselves to each other.”

– John Vucetich, Professor of Biology at Michigan Technological University, wolf expert and lead for the reserach project Wolves and Moose of Isle Royale. (quoted in Vox)

“The clock is ticking. We must find solutions that allow wolves to flourish, even while we balance the needs of hunters and ranchers and others who live and work along with wolves on the landscape. My Pueblo ancestors taught me to live with courage, respect our ecosystems and protect our families – the very same virtues that wolves embody. From our public lands to our vast oceans, and all the creatures that live within them, I will continue to work hard for our nation’s wildlife and its habitats, because we were meant to all coexist on this earth – the only place we all call home.”

– Deb Haaland, U.S. Secretary of the Interior and the first Native American to serve as a cabinet secretary, in an op-ed in February this year entitled: Wolves have walked with us for centuries. States are weakening their protections.

“The song of the dodo, if it had one, is forever unknowable because no human from whom we have testimony ever took the trouble to sit in the Mauritian forest and listen.” – David Quammen, in Song of the Dodo: Island Biogeography in an Age of Extinctions

Thanks so much as always for your interest in my work, and if you found this digest useful, please consider sharing with others who might find it interesting too😊 I'd also love to hear from you. Leave a comment to let me know what you think about this digest, what areas of environmental communication you’re involved in/most interest you, or anything you’d like to see more of in Wild Ones:)

I first encountered the phrase ‘more-than-human world’ in ecological anthropologist David Abram’s fascinating 1996 book, Spell of the Sensuous: Perception and Language in a More-Than-Human World.

This quote comes from Aldo Leopold’s well-known book on environmental ethics: A Sand County Almanac.

These two wolf discourses are just a rough sketch from my reading of Blakeslee’s American Wolf, but for a more in-depth academic dive into wolf discourses, I recommend Aaron T. Phillips’ Bordering Ecosystems: The Rhetorical Function of Characterization in Gray Wolf Management. Environmental Communication, 11(4), 435–451. 2017. And for some excellent reporting on competing wolf discourses, also see Edge Effects Magazine’s recent piece: Who’s afraid of Wisconsin’s wolves.

More so, something I didn’t know was that the USDA (U.S. Department of Agriculture) has an organization called ‘Wildlife Services’ (formerly ‘Animal Damage Control) which works to protect livestock from ‘damage’ by wild animals. In 2020 Wildlife Services killed 381 wolves, and again 324 wolves in 2021. This strikes me as a bit of a disproportionate response, to say the least. While the controversy over state-sanctioned wolf hunts makes it into mainstream news, I rarely hear about the role federal organizations like Wildlife Services play in killing wolves – as well as millions of animals annually in the U.S. – in the name of protecting economic interests. I also wonder how this policy of ‘damage control’ squares with the stated mission of Wildlife Services “to improve the coexistence of people and wildlife.”

Thanks for this, Gavin - a detailed and enjoyable read!