🌿Wild Ones #77: Environmental Communication Digest

"Rubber boots methods in the Anthropocene" + Counter-mapping against palm oil in Indonesia + Walruses on the brink + #SeaTurtleWeek + more!

Hi everyone, welcome back to Wild Ones, a (usually) weekly digest by me, Gavin Lamb, about news, ideas, research, and tips in environmental communication. If you’re new, welcome! You can read more about why I started Wild Ones here. Sign up here to get these digests in your inbox:

Correction to last week’s post: I mistakenly attributed the essay I cited from the Green Fix newsletter —”What's so bad about being an angry woman activist anyway?: It's love AND rage, after all” — to the wrong author. The correct author is

, who also runs , a great climate action newsletter I recommend, especially for climate news, actions steps and ideas!📚 What I’m reading

Rubber Boots Methods for the Anthropocene: Doing Fieldwork in Multispecies Worlds. Edited by Nils Bubandt, Astrid Oberborbeck Andersen, and Rachel Cypher (2022).

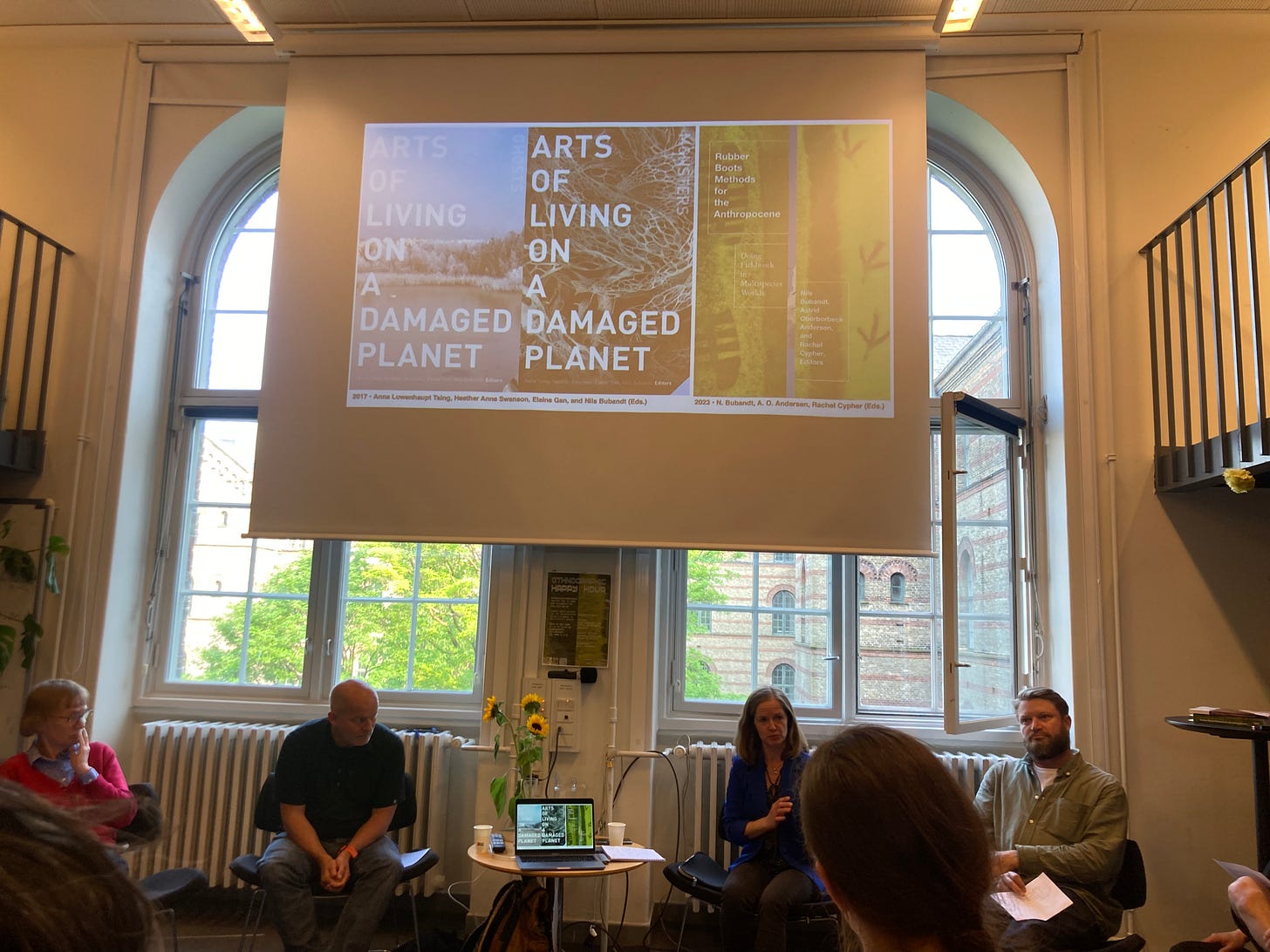

I’m steadily making my way through the chapters of Rubber Boots Methods, and so far the journey has been fascinating. The idea for the book, as the editors write in the acknowledgements, was first brewed at the final conference of the Aarhus University Research on the Anthropocene project. It was envisioned as a companion book to a previous AURA book project from 2017: Arts of Living on a Damaged Planet: Ghosts and Monsters of the Anthropocene. As the titles of both books suggest, the idea of the Anthropocene looms large, and the editors note in the introduction that “The Anthropocene is a contested concept that means many things to many people.”

Looking back at the environmental keywords I’ve written about over the three years I’ve been writing this newsletter, the Anthropocene was one of the first I wrote about. At the time, I used environmental geographer Jamie Lorimer’s framing of ‘the Anthropo-scene,1 which he uses to capture how the term is generating “a flurry of activity with far-reaching ontological, epistemic, political and aesthetic consequences.”

One important consequence of the Anthropocene as a keyword (or buzzword rather), as the editors of Rubber Boots Methods point out, is that it’s compelling researchers to rethink disciplinary boundaries between the social and natural sciences, not just pushing us to think outside the box of old disciplinary divisions, but to rethink these boxes altogether. In other words, if the planetary challenges we face today involve interwoven social and ecological problems, then we need interwoven social-ecological understandings to solve them. As the editors put it:

“It is our claim and point of departure that the changing conditions for human and nonhuman life on Earth—for which the concept of the Anthropocene is a contested and imperfect moniker2—demand new modes of sensing and seeing, new forms of collaboration, and new foci for description in which landscape histories matter” (p.5).

Each of the chapters in Rubber Boots Methods suggests ways to do this. I’m bouncing around the chapters of the book a bit right now, but so far it’s been a journey! For example, I’ve learned from Andrew Matthews’ research how he combines walking and sketching his way through the chestnut and pine groves in Mount Pisano, Italy with GIS analysis and systems modeling to reveal new stories about this Italian landscape. With this interdisciplinary approach, a single tree stump can reveal multi-layered stories on everything from the ecological impacts of Mussolini’s Fascist rule3 to waves of plant diseases into Italy that hitchhiked on global trade routes. As Matthews puts it, “By attending to the morphologies of individual trees, we can learn to imagine dramatic histories that have transformed entire landscapes” (p. 48).

In another chapter, Pierre Du Plessis takes readers to the Kalahari Desert in Botswana where he has spent over ten years doing research with !Nate, Karoha, and Njoxlau, three Indigenous San trackers who now use their skills to track the movements of wildlife for conservation efforts in the Kalahari. With hunting banned, the trackers now enlist their life experience with tracking to work for conservation organizations, conducting the wildlife population surveys needed to establish an official protected wildlife corridor in the region. As Du Plessis writes, tracking enables them to “step into the shoes” of nonhuman others and empathize with their concerns (like an aardvark worried about a hare trying to steal its food), revealing the many dramas animating this desert landscape from other species’ points of view. As Njoxlau puts it to Pierre, “…tracking is good because it tells you that you are here, and that you are not alone.”

The book also examines a collaborative project between biologists, archeologists and anthropologists in the High Arctic of Northwest Greenland with the aim of documenting the past, present and future of human-relations with arctic species. These species included walruses, muskox, and dogs, with whom some ‘hunters have a secret language.’ Here, sledging is one of the key ‘boots’ enabling a research to explore the field. However, to understand “the ways that land and sea come to matter to each other, across scientific, touristic, and Indigenous registers,” an amphibious approach is needed argues Nils Bubandt. Moving into the tidal zone requires a different kind a boot, ‘rubber flippers’ to be exact, enabling movement for research across terrestrial and aquatic spaces. Other chapters explore ‘metaphorical boots’ that open up new ways for researchers to see and understand landscapes, like horse-riding in the Pampas of Argentina, or drip-torches in controlled eucalyptus burns in Australia.

If the Anthropocene calls for more collaborative projects across the social and natural sciences to address the immense challenges of our time, then ‘rubber boots methods’ offers a glimpse into what these interdisciplinary collaborations actually look like in practice across the deserts and forests, muddy earth and airy atmospheres, deep sea zones and nearshore landscapes of the world. “Rubber boots methods,” the editors write in the introduction,

“is the playful name we have given to these more-than-human method experiments across disciplines. The name reflects our practical realization that waterproof footwear was essential in the cold, waterlogged landscapes of the former brown coal mines. The term also grew out of a wish to defend "rubber boots biology," a derogatory term used in Danish biological circles to denote fieldwork-based biological observations of ecosystemic relations. Rubber boots biology (Danish: gummistovle-biologi) has in recent years been marginalized from university education and research, pressured by more prestigious branches of biology, such as laboratory-based microbiology, molecular biology, computational biology, ecosystems modeling, and biotechnology. This marginalization of field-based approaches is part of an overall institutional trend…”

It’s not that big-data generating, system modeling research isn’t critically important, the authors write, since this was precisely the data that helps understand the scope of the immense challenges of our time, from species extinction and ocean acidification, to deforestation and global warming. But from a ‘rubber boots’ perspective, it does raise questions about what gets missed or goes unnoticed when such ‘big data’ stories are priveleged at the expense of closer-to-the-ground (or water) stories:

“We wonder, however, what is lost when scientific knowledge production about changing ecosystems is dominated by sensing from afar and by modeling. What realities and stories, what kinds of critical connections, never make it out of the dust, mud, or water of lived lives and fieldwork observations into research results?…Rubber boots are the metaphorical device through which we call for and invoke the sensitivities, interactions, and histories necessary to bring out these realities and stories.”

I also had the chance to attend the book launch event for Rubber Boots Methods in the Anthropocene at the University of Copenhagen this May. It was fantastic to hear some of the editors and authors talk about the ‘behind-the-scenes’ ideas and stories that went into the making of their chapters in the book.

🎧 What I’m listening to

Data Dialogues: Season 2: Indonesia’s OneMap Policy, from the Open Environmental Data Project:

“This season focuses on Indonesia’s OneMap policy: a decade-long, ongoing effort to resolve land conflict with data. Host Madhuri Karak speaks to everyone from indigenous elders to multispecies ethnographers about their experiences with mapping exercises to delve into the limitations of modern cartography and indigenous struggles over being seen.”

I spent the weekend listening to a fascinating and troubling examination of Indonesia’s OneMap Policy, in Season 2 of Data Dialogues, hosted by Madhuri Karak. As Karak introduces the season:

“Indonesia looms large for anyone who studies agrarian change, forest-based livelihoods, forest rights, indigenous struggles - and learning about what's happening across the oceans in Indonesia. All of this came together for me while working on this season for Data Dialogues which is about maps as a tool for indigenous recognition and mapping as a political process for indigenous sovereignty.”

Host Madhuri Karak takes listeners through a fascinating series of conversations with experts on Indonesia’s OneMap policy including environmental social scientists, journalists, Indigenous leaders, and Indigenous rights policy advocates to ask the question: “…what happens when a sprawling, ambitious policy like OneMap hits the ground.”

For a bit more context, Indonesia’s OneMap Policy emerged in the early 2010s as an effort by global institutions like the UNFCCC and World Bank to enroll Indonesia as a key nation in efforts to “reduce emissions from deforestation and forest degradation” (REDD+). Today, REDD+ is a central to Indonesia’s effort to “contribute to the global temperature goal under the Paris Agreement.” As we learn from Karak’s conversation with Micah Fisher, a researcher of deforestation and land rights policies in Indonesia, REDD+ really took off as an international policy instrument to address climate change after the UNFCCC conference in Bali in 2007.

In the years that followed, REDD+ gained steam in high-level climate policy-making circles around the world as a market-based mechanism for ‘offsetting’ global emissions, especially in Indonesia. In other words, as Karak explains, “global bodies like the UNFCCC and the World Bank figured out a way to outsource climate responsibilities to Indonesia. The idea was deceptively simple: Global North countries would pay Indonesian village communities to not deforest. But you need to know who owns the forest that's being protected so you can then pay them. And that was the role assigned to OneMap.”

NGOs advocating for community land rights in Indonesia saw the rise of REDD+ as an opportunity, arguing that you can’t protect forests without also protecting Indigenous people’s rights to land too. As Karak puts it, “local communities got into the room by saying hey, you can’t map carbon and you can’t map biodiversity hotspots without acknowledging and mapping our land rights too.” Here we learn about growing efforts among Indigenous groups in Indonesia to ‘counter-map’ their territories against the grain of government agencies working off old colonial maps that erased Indigenous land rights, as well as corporations seeking to claim for profit. I had heard about ‘counter-mapping’ before as a literary tactic in nature writing, and wrote about it a couple of years ago here on Wild Ones. But listening to this podcast was the first time I had heard it used in the context of community mapping efforts to push back against the powerful interests of corporations and government agencies.

This is the other part of the story: In Indonesia, these powerful interests are often connected to the explosive expansion of palm oil plantations in the country. The drive to expand palm oil plantations for profit often leads to agencies quickly granting licenses to companies rather than undergo the lengthy process of getting Indigenous maps registered under Indonesia’s national OneMap policy. How are palm oil plantations using maps to override community land rights? And what ‘counter-mapping’ strategies are these communities mobilizing in response? I highly recommend listening to consider these questions, and their wide-ranging implications for understanding the links between climate justice and Indigenous land rights around the world.

👀What I’m watching

“A lone scientist on the coast of the Siberian Arctic finds that warming seas have taken a toll on the walrus migration, as documented in a film by Evgenia Arbugaeva and Maxim Arbugaev. "Haulout" is nominated for Best Documentary Short at the 2023 Academy Awards.”

📰 News and Events

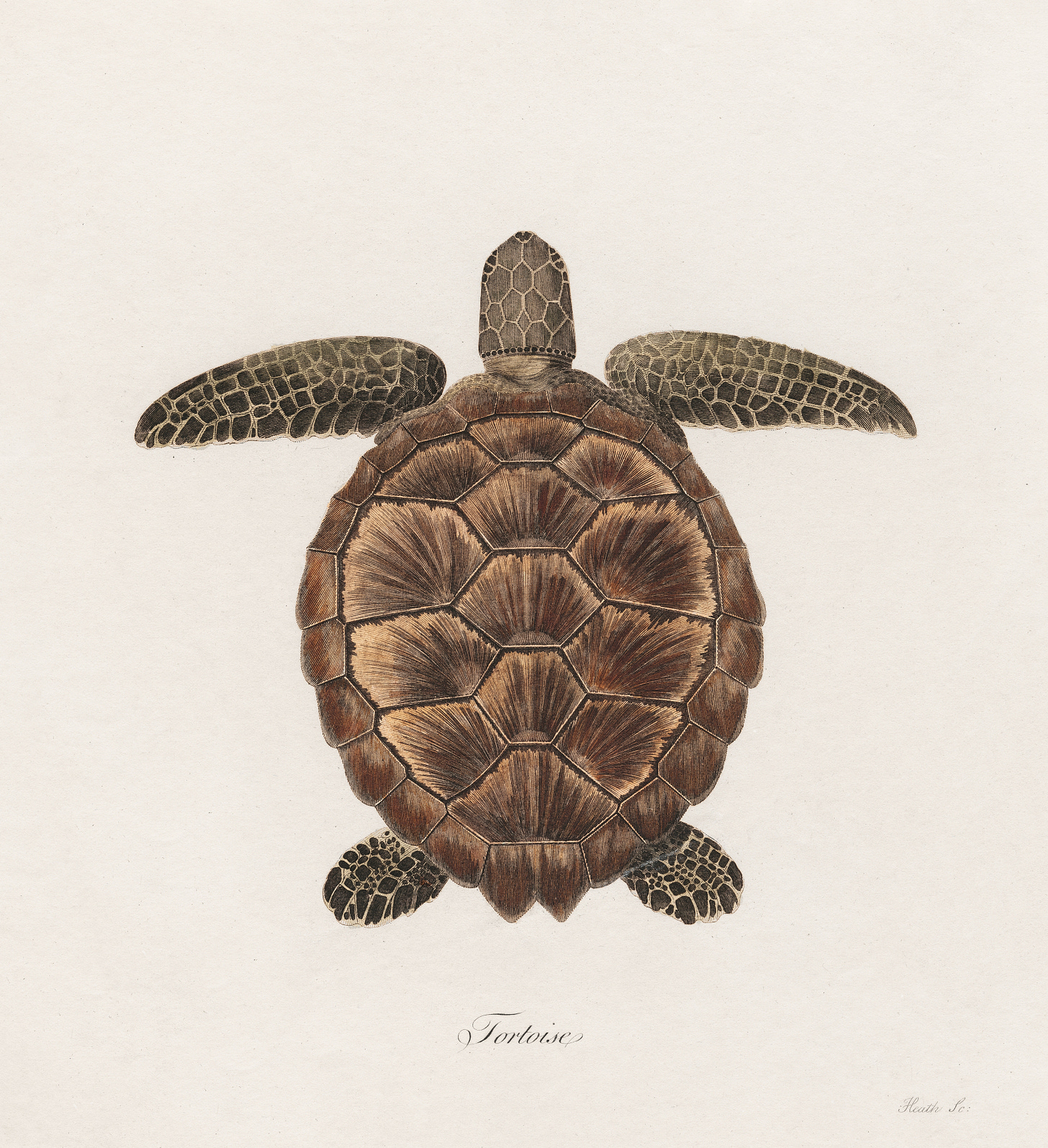

It’s officially #SeaTurtleWeek (June 8-16)! Just in case for new readers that don’t know, my PhD dissertation research was on the nexus of sea turtle conservation and tourism in Hawai‘i, and while doing this research I had the pleasure of learning from sea turtle scientist George Balazs both about his life-long efforts to conserve sea turtles, as well as his advocacy for the crucial role of Indigenous-led conservation in these efforts. This month is also the 50th anniversary of his first visit to the French Frigate Shoals in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands in the first study to monitor green sea turtle nesting there. This initial study in 1973 to understand the health of sea turtle populations in Hawai‘i turned into a decades-long research endeavor that has helped inform efforts to conserve sea turtles around the world as well. Balazs’ work not only reveals the extraordinary lives of sea turtles, but also that there is still so much we have yet to learn from their resilience in the face of tremendous challenges in a changing world. As he writes in a paper from 20174:

"At this 45-year juncture of continuous research focused on the Hawaiian green turtle, the overall goal of conservation investigations should be adjusted to embrace more than the collection, archiving, and publishing of scientific findings. A new era should be initiated that encompasses cultural integration by and for the indigenous Hawaiian people that are themselves linked for millennia to their green turtles. Exactly how this will take place should be left to Hawaiians to decide."

With his permission, I’m also re-sharing a message he wrote to a sea turtle mailing list commemorating the 50th anniversary of his first trip to the French Frigate Shoals below:

“50 Years Ago, on June 1st, 1973, I first set foot at French Frigate Shoals to start a tagging and monitoring study at Hawaii's principal green turtle nesting colony. What began as a 5-year project funded by the State of Hawaii has endured to the present. My Warm Appreciation to all who have been a part of this amazing undertaking over the decades. And to the turtles themselves that have taught us so much about their tenacity, recovery capacity, and ability to adapt to changing conditions. They have also taught me that... time goes fast when you're having fun.

Here's what Ursula Keuper-Bennett and Peter Bennett had to say in 1998 at the 25-year mark of this now half-a-century journey.”

📚 Research

REDD+ policy making in Nepal: toward state-centric, polycentric, or market-oriented governance? By Bryan R. Bushley, in Ecology and Society, 2014.

While listening to the Data Dialogues podcast above on REDD+ policy in Indonesia, I was reminded of the work of my friend Bryan Bushley, who did the fascinating study of REDD+ policy in Nepal cited above. In this paper, he uses social network analysis to examine how different individuals and organizations —governmental agencies, NGOs, educational institutions, civil society organizations, community groups—communicated and collaborated with each other, or not, and why. It is a rich study that shows Bryan’s brilliance at investigating the communication networks, and power relations that underly them, that make or break environmental polices. I first met Bryan in a course on climate justice we took together in 2014 with Naomi Klein while she was a visiting professor at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa. Bryan sadly passed away in 2016, but I was glad to experience his unique combination of intellect, humor and bottomless kindness in the brief two years I knew him. You can read a tribute to him here, and his obituary here.

Slow Violence in the Anthropocene: An Interview with Rob Nixon on Communication, Media, and the Environmental Humanities. By Christensen, M. in Environmental Communication, 12(1), 7–14. (2018).

Christensen: “…what would you say is the overall salience and relevance of this term in research and also in communications?…”

Nixon: “One of the positive things to come out of the Anthropocene is the rise of unprecedented conversations among a very broad spectrum of disciplines. Previously, it would have been pretty much a world historic event to have had a Victorian literature scholar in conversation with an atmospheric chemist. And, so I do feel that the type of conversations that are being generated within academe, and to a limited extend, have spilled over into public culture in terms of film and museum exhibitions, I do think that the Anthropocene has been an engine for connectedness.”

The Place of the Teacher: Environmental Communication and Transportive Pedagogy. By Erin Hawley, Gabi Mocatta & Tema Milstein. In Environmental Communication (2023).

“Environmental communication pedagogy aims to build core competencies that empower students to solve wicked problems and participate in pro-environmental action. The “ethical duty” of the field (Cox, 2007) extends to educators, who, like environmental communication researchers and practitioners, seek to empower others to lead change during a time of ecological crisis…Educators in this field seek to help their students participate in environmental conversations taking place in and across ecocultures, media landscapes, and transforming public spheres, enabling them to become aware, ethical, and effective environmental communicators and change-makers” (p. 339).

💡 Ideas

“Doughnut Economics is all about action. We’re not sitting having academic debates back and forth about the meaning of words,” Raworth said when I put these criticisms to her. “It’s time to be propositional, and sometimes the best form of protest is to propose something new.”

What it means to practise values-based research: Environmental scientist Max Liboiron ties principles of humility and accountability to research that respects people and their relationship with the land. By Spoorthy Raman in Nature.

Raman: How should other researchers use the anti-colonizing lens in their science and work with communities?

Liboiron: Our bumper sticker for that would be, ‘Don’t be a jerk!’ The first step is to do your homework: understand the community, what it needs and whether your skills and research would be useful to it. Meet people on their terms. Take them seriously when they have other forms of knowledge. And hire people and pay them what they are worth. Don’t lead with individualism and think you own everything, when the data come from Indigenous land. Have a reputation for giving data back and doing it in a timely manner.

Writing the Animal Other: Beyond Anthropomorphism. By Heather Durham in Brevity Magazine.

“Some of my earliest writing advice was to beware anthropomorphism. Whenever an animal flew, stalked, or swam into an essay, I’d receive that warning at least once in any critique. Having come to writing in middle age after experiences as a naturalist, park ranger, field biologist, and graduate student of ecology, this happened often. Early on, I accepted the admonishment as a cardinal rule of nonfiction writing, an extension of always tell the truth. To write animals with human characteristics, motivations, or—gasp—emotions, was to lie.”

🗃️ From the Archive

🌿Wild Ones #26: Environmental Communication Digest

Counter-mapping + Visual risk communication + "Greentrolling" + Ecolinguistics & Ecocriticism + More!

"So ‘counter mapping’ is a way of remapping a landscape with a view to pushing back against power. I’m not sure if that’s what [my book] The Wild Places does, but I certainly thought of it as unrolling a different kind of map" – Robert Macfarlane

💬 Quote I’m thinking about

“Many words are walked in the world. Many worlds are made. Many worlds make us. There are words and worlds that are lies and injustices. There are words and worlds that are truthful and true. In the world of the powerful there is room only for the big and their helpers. In the world we want, everybody fits. The world we want is a world in which many worlds fit.”

– ‘Fourth Declaration of the Lacandon Jungle’ (1996) Zapatista National Liberation Army (Ejército Zapatista de Liberación Nacional, EZLN), translation by Mario Blaser and Marisol de la Cadena.

Thanks so much as always for your interest in my work, and if you found this digest useful, please consider sharing with others who might find it interesting too😊 I'd also love to hear from you. Leave a comment to let me know what you think about this digest, what areas of environmental communication you’re involved in/most interest you, or anything you’d like to see more of in Wild Ones:)

Jamie Lorimer attributes the first use of the term “Anthropo-scene” to the environmental geographer Noel Castree in his article Changing the Anthropo(s)cene: Geographers, global environmental change and the politics of knowledge.

On the contested Anthropocene, the editors of Rubber Boots point to the work of Donna Haraway, Kathryn Yusoff, and Marisol de la Cadena.

As Matthews tells it, Bruno Mussolini wanted Italian people to be more ‘martial’ and so opened private lands to hunters and mushroom pickers, leading to creation of extensive pathways throughout the rural Italian landscape, making “the countryside more accessible than in most countries” (p. 39).

If you’re interested in exploring some of the many research articles on Hawaiian green sea turtles that George Balazs’ decades of research in Hawai‘i has made possible, starting way back in June 1973, Balazs suggests these as a good place to start: