🌿Wild Ones #87: Environmental Communication Digest

Naomi Klein's Doppelganger: A trip into the mirror world + Puffing in Iceland + Conservation jargon + A new whale alphabet? + More!

Hi everyone, welcome back to Wild Ones, a digest by me, Gavin Lamb, about news, ideas, research, and tips in environmental communication. If you’re new, welcome! You can read more about why I started Wild Ones here. Sign up here to get these digests in your inbox:

📚 What I’m reading

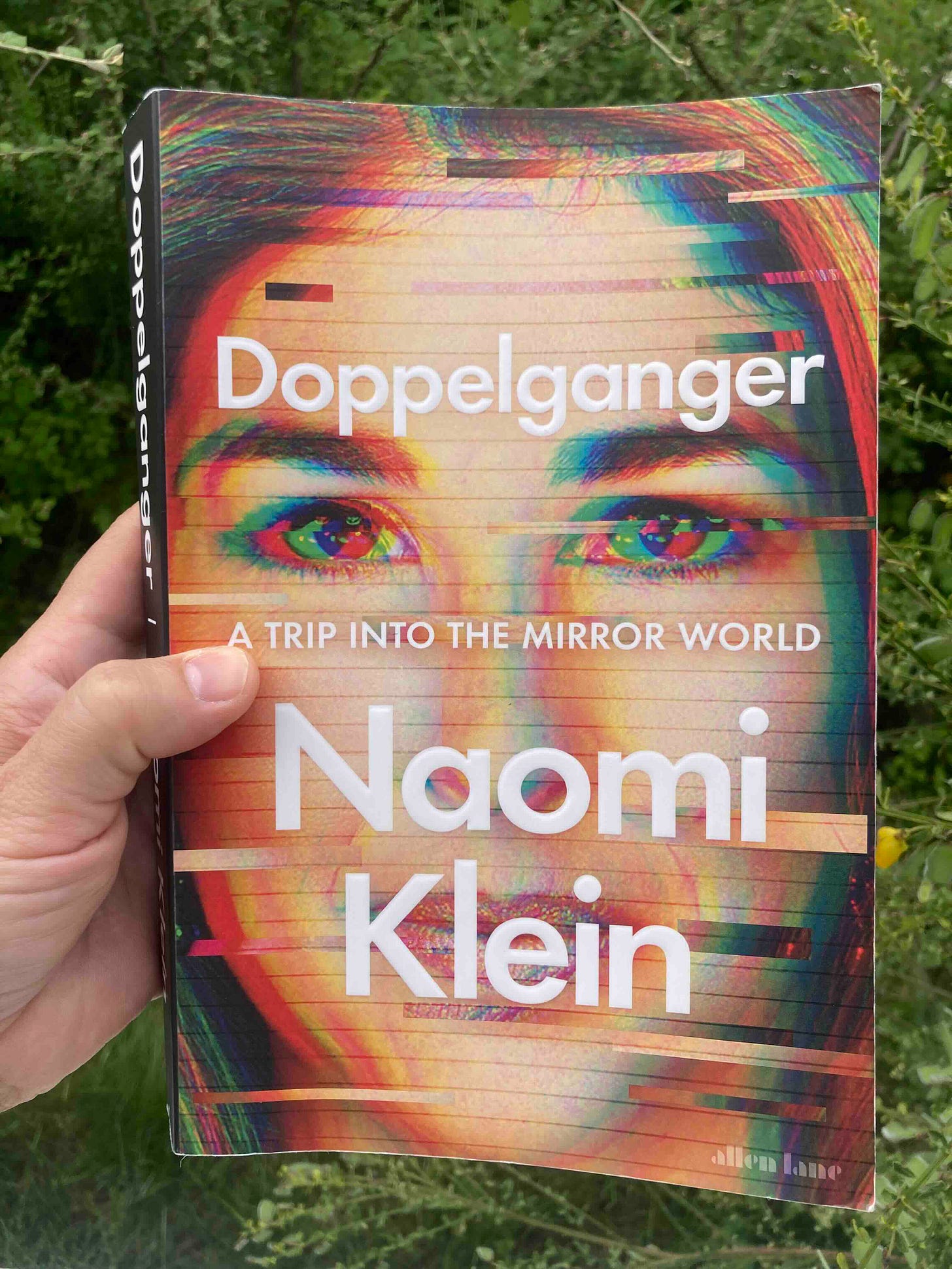

Doppelganger: A Trip into the Mirror World. By Naomi Klein (2023).

“For my entire adult life I have been writing about the severing of signs from meaning. I had no idea, though, of how far it would go….” –Naomi Klein, in Doppelganger.

I’ve been a fan of Naomi Klein’s work for years since reading her book the Shock Doctrine way back in 2008. Actually, if I think about it, a big part of my shift in research focus to environmental communication during my Ph.D. was a consequence of taking a seminar with her to discuss her book This Changes Everything: Capitalism vs. The Climate while she was a visiting professor at the University of Hawai‘i ten years ago. Klein’s newest book, Doppelganger: A Trip into the Mirror World, takes her long-time experience being confused with the liberal feminist turned right-wing conspiracy theorist Naomi Wolf as a point of departure for examining the explosion of social media-fuelled conspiracy culture, especially in the wake of the covid pandemic. The book delves into her personal life in ways her other books haven’t and so I found it fascinating to read about how she navigates the weird experience of having a ‘doppelganger’ in the world. I think it’s one of her most powerful books, at least from the perspective of someone who thinks a lot about the ties between language and action in a time when these ties seem to be becoming more explicitly questioned in environmental movements and climate campaigns (think Greta’s ‘blah blah blah” speech for example).

One of the important themes in the book, or at least one that I’ve kept thinking about since finishing the book, was Klein’s examination of how contemporary ‘conspiracy culture’ —to call it ‘conspiracy theory,’ she writes, would suggest a kind of argumentative coherence to what is really “conspiracy without a theory, it’s throwing a lot of stuff at the wall, seeing what sticks”— has opened up an ever-widening gap between language and reality, or as she puts it, a “violent rupture between words and world.”

For example, Klein examines how conspiracy influencers on Instagram and TikTok—especially in the ‘conspirituality’ space that blends various health and wellness, environmental, and political conspiracies — perform a doppelganger version of investigative journalism, “imitating many of its stylistic conventions while hopping over its accuracy guardrails” (p. 224), in crafting a sort of ‘conspiracy smoothie’ for their online audience. The ingredients in this conspiracy smoothie seem at first like unlikely pairings as they “bring together many disparate political and cultural strains” (p. 101) (from a ‘conspiratorial far-right’ to ‘alternative health subcultures usually associated with the green left’) that have mostly operated as disconnected subcultures. But the shared idea of the Covid pandemic, viewed as a “plot by Davos elites to push a reengineered society under the banner of the ‘Great Reset,’” seemed to function like a powerful gravitational field collapsing disparate conspiracies together into a ‘conspiracy singularity’ notes Klein, a term coined by journalist Anna Merlan who argues that in the wake of the pandemic and protests for racial justice in 2020, “conspiracy communities are bleeding into each other, merging into one gigantic mass of suspicion.”

I didn’t really consider (or rather, avoided thinking about) this conspiracy smoothie until a couple of years ago when I started learning more about social media research in linguistics and environmental communication on topics like post-truth environmentalism in an age of ‘platform capitalism’, hashtag environmental communication during the Covid pandemic, and an interesting conference presentation by linguistic anthropologist Catherine Tebaldi in 2022 on the far right eco-discourses of the ‘tradwife’ movement and ‘right wing hippies' circulating on social media.

Klein writes that she tried to ignore this conspiracy smoothie for a while too, but it became increasingly difficult to do so after the constant public confusion between her and her ‘Great Reset’ doppelganger (Wolf), as well the increasing number of conspiratorial ‘researchers’ using her 2007 thesis of ‘The Shock Doctrine’ to bolster their conspiratorial claims, albeit with different conspiratorial ingredients depending on which subculture of the fascist far right/New Age left they’re coming from. In her 2007 book, the Shock Doctrine referred to ‘a state of shock’ that “happens to us—individually or as a society—when we experience a sudden and unprecedented event [like a financial crisis, a hurricane, a war, a pandemic…] for which we do not yet have an adequate explanation. At its essence, a shock is the gap that opens up between event and existing narratives to explain that event” (p. 7).

Klein’s book examined how ‘disaster capitalists’ swoop in to benefit from such shocks by filling these narrative gaps with their own “preexisting wish lists and simplistic stories of good and evil” (p. 8). The confusion and discomfort experienced in the ‘nothingness of the gap’ leaves audiences thirsting for meaning especially receptive to such stories. And these gaps act like oxygen fuelling conspiracy culture to spread. Klein emphasizes that there are clearly conspiracies that we can prove: big oil conspiring to fund climate denial and delay, suppressing climate communication for decades with full knowledge that fossil fuels are warming the planet with catastrophic consequences is a scandal, a conspiracy that we can prove. It’s not conspiracy theory, Klein notes, it’s just fossil capitalism doing its thing. Conspiracy culture, on the other hand, while detached from reality, does serve an important purpose: it functions as an engine of distraction from the very reality-based scandals of disaster capitalism.

The story of disaster capitalism that Klein tells in The Shock Doctrine offers a structural critique of how a predatory capitalist system inevitably tries to operate whenever societal ‘shocks’ occur. But drawing on the work of Rutgers journalism and media scholar Jack Bratich, Klein writes that in a western liberal culture that has stewed in cultural narratives that locate agency/power (and thus responsibility) in the individual, the individual (or group of individuals) tends to be seen as the potential hero or villain of most stories about what’s right or wrong with the world. Within such a cultural framework that hyper-individualizes power, it becomes much harder for stories that critique power-in-structures to resonate, and easier for stories that praise or blame power-in-individuals/groups to take hold, especially in the ‘meaning vacuum’ that flows downstream from a state of shock.

So, in reflecting on how the fact-checked narratives of voracious shock capitalism she told in her past work like No Logo, The Shock Doctrine, and This Changes Everything, were ransacked for ingredients to throw into new conspiracy smoothies, Klein realized she has also been telling a second, underlying story throughout her work. This ‘second story’ she was telling was not just about a narrative gap that opens up in times of shock when the chaos of the moment leaves people searching for explanations, but about a much deeper rupture between words and action:

The story beneath the story was the normalization of the disassociation between words from reality, which could only usher in the era of irony and flat detachment, because those seemed like the only self-respecting postures to adopt in a world in which everyone was lying all the time.”

Concerns about the erosion of shared reality in a ‘post-truth’ society, amplified by a social-media enabled conspiracy culture may not be a radically new observation. But Klein takes this exploration of doppelganger conspiracy culture in a direction I haven’t considered much, which is the psychological experience of what ‘doppelganging’ does to our sense of self. She describes a university course she teaches called ‘The Corporate Self.’ The course begins with students writing about the first time they heard about the concept of ‘being a brand’—learning to package and sell one’s experiences and hardships as ‘consumable commodities’ in the college admissions essay is a popular topic—and from there students often describe their sense of two diverging selves: a complex authentic self and a second simplified and marketable self.

Doppelganging, or this strategic doubling of the self, is a three-step-process where one first ‘partitions’ their ideal self from their real self—for example through a college admissions essay, a version of one’s identity emphasized in face-to-face conversation with others, or one’s social media avatar on Instagram or Facebook—and then ‘performs’ this ideal self in a way that might best appease the perceived desires of their intended audience. Finally, in the third step, Klein says, people ‘project’ the “unwanted and dangerous parts of themselves onto others (the unenlightened, the problematic, the deplorable, the “not me” that sharpens the borders of the “me”) (p. 57). In the aftermath of this three-step doppelganging process, both beneficial and bad consequences for the ‘real self’ can ensue, from fame and fortune on one extreme, to identity theft and public shaming on the other.1 Klein explores how conspiracy culture thrives on this doppelganging three-step ‘dance’ (not to be confused with Anand Giridharadas’ thought-leader three-step:).

Projection, the final stage of this three-step, is especially important as it involves a form of mirroring an ideal self against unideal others, and as a consequence, hardens differences between individuals or groups of individuals through comparison with one side’s ‘evil twin.’ But almost everyone with an online presence participates in this dance to some degree, whether it’s in everyday conversation, work emails, or especially amplified in social media like Instagram and TikTok. Learning to curate and brand one’s digital double(s) is increasingly becoming a key aspect of the human condition in the 21st century. But the ‘story beneath the story’ of the doppelganger three-step, for Klein, is that it is part of an emerging post-truth conspiracy culture that makes communicating in today’s world feel increasingly like ‘quicksand.’ This is because of…

“…the confusion between saying/clicking/posting and doing. The tension between the virtual nature of lives led in the blue glow of screens and the reality of the embodied labor (digging, harvesting, soldering, sewing, scrubbing, boxing, hauling, delivering) and material inputs (oil, gas, coal, copper, lithium, cobalt, sand, trees) that make it all possible” (pp. 152-153).

Naomi Klein tells the story of this rupture between words and world like a psychological thriller. If words no longer have the effect we once thought they did, there is a kind of ‘speechlessness’ that overtakes us: “Words are still useful for practical purposes, like arranging after-school pickups and making grocery lists and writing catchy songs,” writes Klein, “but for changing the world?”

She recalls a conversation with the climate writer Bill McKibben who tells her that the reason he started his climate organization 350.org was because he steadily lost faith in the power of his writing articles and books to make any tangible difference in halting the climate crisis. Writing is all fine and good, but when it comes down to it, it’s really “movements of people who change the world,” he told Klein. But in reflecting on this conversation, Klein poses the challenge slightly differently:

“…here's the question that has been eating away at me: What if our books, and our movements as they are currently constructed (often in ways that resemble corporate brands), are only changing words? What if words—written on the page or shouted in protest—change only what people and institutions say, and not what they do?” (p. 152).

Doppelganging, Klein worries, only fuels this challenge to change the world with words because it draws our focus into creating, curating and modifying an endlessly growing simulacra of wordy-worlds, performing ideal linguistic versions of ourselves, our institutions and the world, rather than actually creating or changing them in the real world. She points to a strange paradox of how this doppelganging process seems to at once ‘overinflate’ our sense of self in the world, while at the same time deflating our sense of agency to do anything to change it. As Klein writes, “Some of the climate scientists whose work I most respect have come around to an understanding that there is an intimate relationship between our overinflated selves and our under-cared-for planet” (p. 324).

This doppelganging three-step (partitioning, performing, projecting) really turns out to be a ‘dance of avoidance,’ Klein argues. But, she asks, avoiding what?

In ratcheting up hyper-individualism, this dance of avoidance obscures the links of interdependence between individuals and the social and ecological life support systems they depend on for their well-being and survival, Klein argues. Learning how this ‘dance of avoidance’ actually works is one of the main things studying doppelganger conspiracy culture can teach us. Towards the end of the book, there is a particular passage I’ve been mulling over the past couple of weeks. Klein writes,

“The more I looked at doppelgangers and the messages they carry, both personally and politically, the more relevant that knowledge seemed to our prospects of becoming the kinds of people capable of getting off our treacherous path….Performing and partitioning and projecting are the individual steps that make up the dance of avoidance. What is being avoided? I think its our true doppelganger. What Daisy Hildyard calls our "second body" the one enmeshed with wars and whales, the one benefiting from the genocides of the past and adding our little drops of poison to the great die-offs of the future. The second body that perpetually mines the Shadow Lands for its comforts and conveniences” (p. 322).

Our ‘true doppelganger’ Klein argues, is this larger ‘second body’ that we dance with, a shadow self that our conscious ‘first body’ doesn’t have to think about, but which it depends on for its well-being and survival. In her book, The Second Body, Daisy Hildyard describes our shadowy body double like this:

“You are stuck in your body right here, but in a technical way you could be said to be in India and Iraq, you are in the sky causing storms, and you are in the sea herding whales towards the beach. You probably don’t feel your body in those places: it is as if you have two distinct bodies. You have an individual body in which you exist, eat, sleep, and go about your day-to-day life. You also have a second body which has an impact on foreign countries and on whales, a body which is not so solid as the other one, but much larger.”

Much of what being human means today in our contemporary global culture and economy, Klein writes, involves learning to avoid listening to, seeing and experiencing this much larger, more diffuse second body that provides the conditions of existence for our first body’s everyday actions (like driving to work or shopping at a grocery store). While our first body fills up the gas tank or flips the light switch, our larger second body enables these mundane actions “by traversing studiously denied parallel worlds on our behalf, extracting and manufacturing the resources and good that make it all possible” (p. 244).

When I read this I couldn’t help thinking of Val Plumwood’s essay on Shadow Places. As the Shadow Places Network, a network of scholars who build on Plumwood’s concept of shadow places, use the term: “Shadow places are physical sites that bear the burden of global climate change and other environmentally and socially degrading forces; these places, and their communities, are forgotten or repressed in the prevailing western mind.” Plumwood was especially concerned with ‘a dominant global economy and culture,’ and western modes of individualistic environmentalism in particular, that work by

“encouraging us to direct our honouring of place towards an ‘official’ singular idealised place consciously identified with self, while disregarding the many unrecognised, shadow places that provide our material and ecological support, most of which, in a global market, are likely to elude our knowledge and responsibility. This is not an ecological form of consciousness.”

In contrast, a “form of place consciousness most appropriate to contemporary planetary ecological consciousness,” Plumwood argues, would be one that encourages “connection, knowledge, care and responsibility…for multiple places.” Notions of community that are valued in such a hyper-individualistic culture tend to idealize a form of ‘self-sufficiency’ that “neglects or suppresses the key justice (north/south) issue of relationship with other communities—downstream communities especially. Taking responsibility for remote places requires strong institutional and community networking arrangements.”

If rebuilding community networking arrangements between ‘official’ places’ and their doppelganger ‘shadow places’ is key, as Plumwood suggests, then how should we go about using communication to change course, especially if words seem to be losing the power to change things we once thought they had? For Klein, ‘getting off our treacherous path’ will involve cultivating modes of communication that rebalance the tension between our desires for “separation and distinctness” on the one hand, and for “unity and community” on the other, especially in a culture that places so much value on the former. As Klein puts it, “The tension is fruitful and does not need to be resolved” (p. 329).

Communication that clarifies and make sense of this tension, rather than dismisses it or exacerbates it, can help to bridge the ‘meaning vacuums’ that arise in times of crisis. But without investing in the communicative infrastructure of inter-place responsibility and connection, Klein warns, ‘official’ places and their supposedly self-sufficient selves will continue to imagine away their interdependence with a growing number shadow places, or doppelganger ‘sacrifice zones.’ As Klein writes,

“If our situation seems uniquely challenging (and on bad days, borderline hopeless), it likely has to do with how much we have come to expect from our individual selves, combined with the brokenness of structures—trade unions, close-knit neighbourhoods, functioning local media, and so on—that once made it easier to do things together. And yet even in these unstable times, I do think it’s possible to overcome some of that fragmentation and to weave ourselves together in new ways.” (p. 328).

I’m struggling with where to end this post since there’s a lot more in Naomi Klein’s book Doppelganger relevant to environmental communication I’d like to explore more here. But to avoid rambling on I think I’ll save that for a future post:) In the meantime, I shared this before but I recommend this fascinating interview with Naomi Klein on the ‘Between The Covers’ podcast from last year where she discusses ideas from her book in depth (it’s over two hours long!):

Naomi Klein: Doppelganger: Part One. Between The Covers: Conversations with writers in fiction, non-fiction, and poetry. Hosted by David Naimon.

🎧 What I’m listening to

The Irish Language: What the Irish language tells us about the world. An interview with Manchán Magan about his book Thirty-Two Words for Field: Lost Words of the Irish Landscape. On BBC’s Word of Mouth podcast.

🐳Scientists Find an ‘Alphabet’ in Whale Songs: Sperm whales rattle off pulses of clicks while swimming together, raising the possibility that they’re communicating in a complex language. Carl Zimmer, NYTimes. May 7, 2024 (Read the research article in Nature here: “Contextual and combinatorial structure in sperm whale vocalisations”)

The Interview: This Scientist Has an Antidote to Our Climate Delusions. NYTimes. (May 18, 2024).

“First of all, I don’t think there’s any one way we should be communicating about climate. Some people are very motivated by the bad news. They’re like: “Whoa, that’s terrifying. What can I do to prevent the worst-case scenario?” Some people need that jolt, and that’s what gets them going. Some people are overwhelmed by that and don’t know where to start. Sixty-two percent of adults in the U.S. say they feel a personal sense of responsibility to help reduce global warming, but 51 percent say they don’t know where to start. So to me, the question is how do we harness and support these millions of people in this country who would like to be a part of the solutions? We have moved beyond the platitudes of reduce, reuse, recycle. People don’t even pay attention to the first “r” there. But how can we create a culture where everyone has a role to play?” – Ayana Elizabeth Johnson

👀What I’m watching

Puffing, directed by Jessica Bishopp: “Every summer, on a remote island off the coast of Iceland, young puffins leaving their nests for the first time often get lost in the town, mistaking the harbor lights for the moon rising over the ocean. In this coming-of-age documentary, we follow two teenagers, Birta and Selma, as they drive through town rescuing pufflings who have lost their way. Illuminating the challenge of setting out into an uncertain world, this film explores the delicate interplay of wild and human lives.”

Also watching:

The Magnitude of All Things (just the trailer for now): “A cinematic exploration of the emotional and psychological dimensions of climate change: When Jennifer Abbott lost her sister to cancer, her sorrow opened her up to the profound gravity of climate breakdown, drawing intimate parallels between the experiences of grief—both personal and planetary. Stories from the frontlines of climate change merge with recollections from the filmmaker’s childhood on Ontario’s Georgian Bay. What do these stories have in common? The answer, surprisingly, is everything.”

How an Industry Revolutionised Itself. An interview with Dani Hill Hansen, sustainable design engineer, architect and co-author of The Reduction Roadmap. On Planet: Critical. (May 8, 2024)

The trial that could change the fate of the Guajajara Indigenous people. By Mongabay.: “Mongabay video screening at Chile’s Supreme Court expected to help landmark verdict in Brazil.”

📰 News and Events

Youth activists win ‘unprecedented’ climate settlement in Hawaii: State’s transport department given a 2045 deadline to fully decarbonize and achieve zero emissions under agreement. By Dharna Noor and Lois Beckett in the Guardian.

New Climate Communication Report📑: International Public Opinion on Climate Change: Extreme Weather and Vulnerability, 2023. Yale Program on Climate Change Communication (May 2024).

How Claudia Sheinbaum Could Change Mexico: A climate scientist is heavily favored to win Sunday’s presidential election. By Kate Aronoff in The New Republic. (May 31, 2024).

New Course!🎓: Foundations Series in Environmental Communication. From the International Environmental Communication Association (IECA). I tend not to share events, tools or courses that require a fee, but in this case I've taken online courses from IECA and found them to be excellent. Here is a short video with an overview of the three-course series.

Research or Lobbying? New Documents Reveal What Fossil Fuel Companies Are Really Paying for at Top Universities. By Molly Taft in Drilled (April 30, 2024):

“One spreadsheet included in the tranche of released documents lists meticulous details of each of BP’s partnerships with Tufts, Harvard, and Princeton. The spreadsheet includes ranking the universities’ research programs as aligned with BP’s “strategic priorities”—like the “shift to gas,” “advantaged oil” (an industry term used to describe the most desirable oil to be extracted during the energy transition). The spreadsheet also includes details like the number of graduates hired from each school by BP, the number of visit days or meetings for BP executives, and scoring each academic institution on its “Industrial Relations Strategy Maturity” (all schools scored a “Medium” ranking.)”

📚 Research

New Book📚: Is Cargill Inc. Really the answer to world hunger? By Richard Alexander. (2024)

“…The book focuses on what Cargill says they do and it investigates the manner in which they say they are doing things. It discusses how the company, Cargill, is keen to present itself as a sustainable corporation. The story it presents to the world maintains that it protects animal welfare, the environment and people, among other things, in all its operations. The language it employs on its corporate websites is subjected to close analysis. The book describes how from an ecological and economic perspective Cargill has enveloped the global food production system with its network of offices and facilities. Along the way, its various activities are held to have contributed immensely to the ecological and environmental degradation of the physical world.”

New Book📚: Science v. Story: Narrative Strategies for Science Communicators. By Emma Frances Bloomfield, University of California University Press.

“Science v. Story analyzes four scientific controversies—climate change, evolution, vaccination, and COVID-19—through the lens of storytelling. Instead of viewing stories as adversaries to scientific practices, Emma Frances Bloomfield demonstrates how storytelling is integral to science communication. Drawing from narrative theory and rhetorical studies, Science v. Story examines scientific stories and rival stories, including disingenuous rival stories that undermine scientific conclusions and productive rival stories that work to make science more inclusive.” (Also see: an interesting review of the book by environmental communication scholar José Castro-Sotomayor)

New Article📝: The commodification of (bad) weather: Destination branding of the Faroe Islands. By Hanna Birkelund Nilsson in Language and Communication.

New Article📝: The importance of understanding the multiple dimensions of power in stakeholder participation for effective biodiversity conservation. By L. Lécuyer, E. Balian, J. R. A. Butler, C. Barnaud, S. Calla, B. Locatelli, J. Newig, J. Pettit, D. Pound, F. Quétier, V. Salvatori, Y. Von Korff, J. C. Young (2024). In People and Nature.

New Article📝: “Got to get ourselves back to the garden”: Sustainability transformations and the power of positive environmental communication. By Tema Milstein, Cathy Sherry, John Carr & Maggie Siebert. In Journal of Environmental Planning and Management:

“…The campus food garden, with its growth and seasons, visible labor, multiplicity of projects, attractive bursting forth of food (like forbidden fruits of knowledge), and biotic complexity, helps reintegrate more-than-human knowledges and methods. Within the almost fetishistically maintained space of the average campus, grassroots sustainable food garden management tacitly critiques the latent material-symbolic discourse of human mastery over “nature” manifested in dominant landscaping practices of reordering, tidying, and manicuring – a sisyphean effort to control and exclude other species and ecological processes classified as out of place in spaces of higher learning.”

New Article📝: Diving into a sea of knowledge: empowering teachers to enhance ocean literacy in primary schools through an ocean education training program. By Cátia Freitasa, Paul Venzo, Alecia Bellgrove, & Prue Francis. In Environmental Education Research:

“…educators in this study highlighted how students became the ‘teachers’ and shared their new knowledge with family and friends, which can be a first step to bringing together intergenerational learning and environmental advocacy (Lawson et al. Citation2018). Communication is a fundamental element of environmental literacy (McKinley, Burdon, and Shellock Citation2023). Therefore, appropriate, effective, and meaningful communication starting from a young age may engage and empower people to take environmental action and increase ocean literacy from local to global scales.”

💡 Ideas

On rejecting the Anthropocene:

Why it was right to reject the Anthropocene as a geological epoch. By Mark Maslin, Matthew Edgeworth, Erle C. Ellis & Philip L. Gibbard in Nature. (April 30, 2024)

Beyond the Anthropocene: We must rethink our epoch. By Sophie Chao in IAI News. (April 8, 2024): “We ought not to search for a single “official” name for our geological epoch – especially since it is an epoch experienced differently by different beings, both human and non-human.”

Why a new literary prize for climate fiction will make a difference. By Tori Tsui in New Scientist (May 15, 2024).

Time to Let This Conservation Jargon Go Extinct?: Bad communication can slow or hinder efforts to protect wild species and spaces. We can fix that. By John R. Platt in The Revelator (April 17, 2024):

“As a conservation journalist, I read a lot of scientific papers, reports and press releases looking for story ideas. And even after doing this for nearly 20 years, many of those documents leave me scratching my head. It’s not the conservation aspects that confuse me. It’s the jargon — the overly specific language members of a profession use to communicate among themselves that often makes little or no sense to the public (or even well-versed reporters).”

How the recycling symbol lost its meaning: Corporations sold Americans on the chasing arrows — while stripping the logo of its worth. By Kate Yoder in Grist.

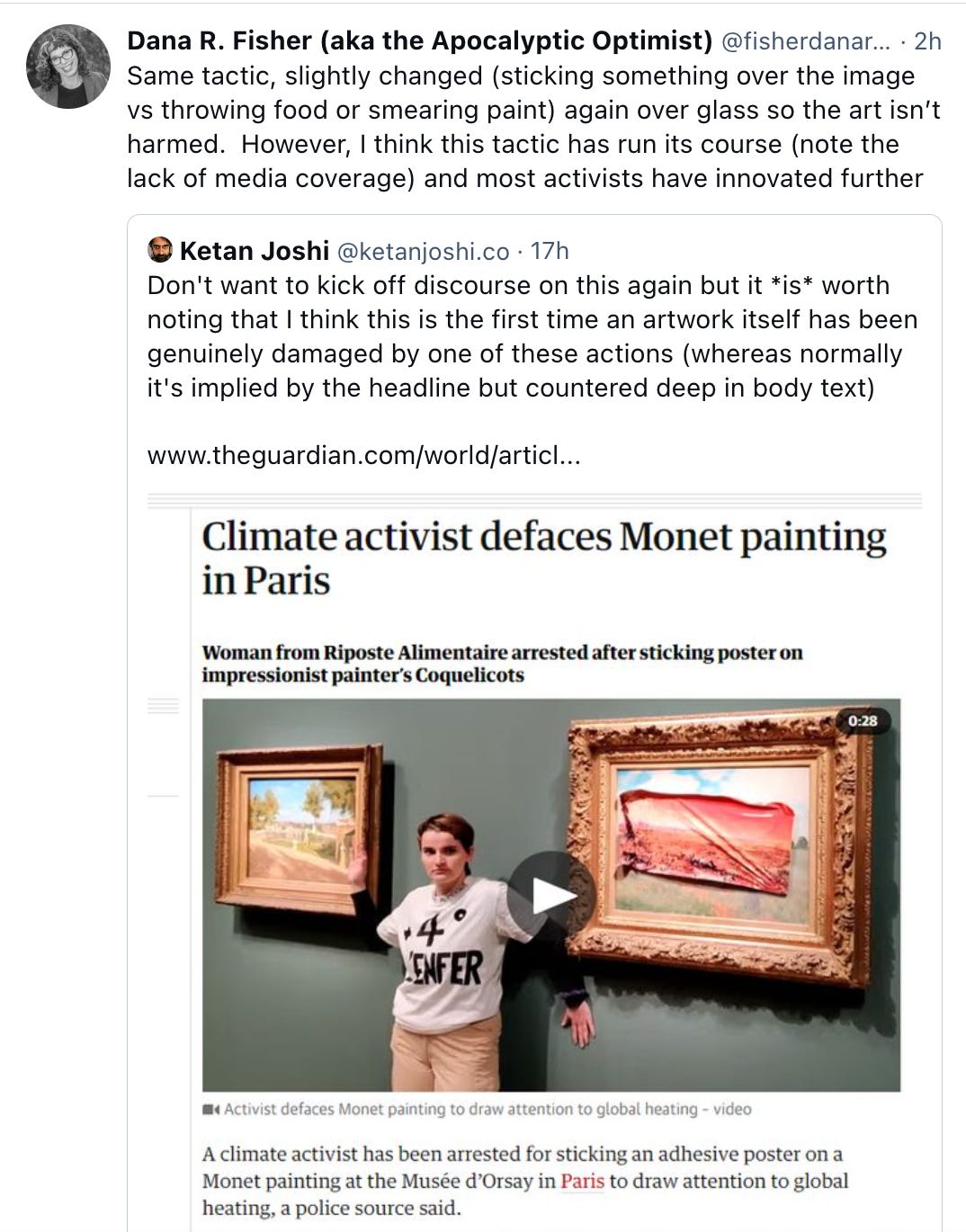

Climate protest tactics and throwing soup at/sticking posters on/spraying cornflour on famous paintings and heritage sites. An activist with the French climate activist network Riposte Alimentaire stuck an adhesive poster depicting a drought-ridden landscape over Monet’s painting Les Coquelicots at the at the Musée d’Orsay in Paris on Saturday. I wrote a bit about “#soupgate” in 2022 and the different reactions to Just Stop Oil activists throwing tomato soup at Vincent van Gogh’s Sunflowers in the National Gallery in London. After the the Just Stop Oil ‘Van Gogh #soupgate’ action in 2022, George Monbiot wrote an interesting opinion piece in the Guardian defending the protest tactic.

Similar news headlines also popped up recently when Just Stop Oil activists sprayed orange cornflower on the stones at Stonehenge. Sarah Kerr, Sarah Kerr, a lecturer in Archaeology and Radical Humanities at University College Cork who studies the intersection of climate change and heritage culture, wrote short piece about it in The Conversation noting that “greater awareness of heritage loss can raise consciousness of the climate crisis and prompt action.”

But climate social scientist Dana Fisher recently questioned whether such controversial protest tactics still generate the intended effects (more media coverage of the climate crisis). Interestingly, as the climate communication researcher Ketan Joshi points out, whenever these tactics are reported on in the media, the news headlines invariably claim the paintings are “defaced,” “attacked” or “vandalized” by activists, burying in the story (or adding in a later addendum as in the recent Guardian piece), that the paintings are protected by glass and were not damaged.

I have Fisher’s newest book on climate activism, Saving Ourselves, on my 2024 book list, but she recently wrote an article in The Conversation sharing some ideas from the book, arguing against the ‘big myth’ that “confrontational climate activism doesn’t work.’ As Fisher writes, “Even though the radical flank of the climate movement is not particularly popular with the general public, there is no evidence that it is turning off other activists in the movement. In fact, there is reason to believe that confrontational acts can help mobilize sympathizers to support more moderate efforts of the climate movement.” Here is Fisher’s article, as well as a couple of interesting related commentaries:

Climate activists aren’t just young people – dispelling 3 big myths for Earth Day. By Dana Fisher in the Conversation. (April 2, 2024).

How effective are climate protests at swaying policy — and what could make a difference? “Why people take to the streets to march against global heating is relatively well documented. But it’s unclear why certain tactics work better than others in reaching the public and policymakers.” By Dana R. Fisher, Oscar Berglund & Colin J. Davis, in Nature. (November, 2023).

What the climate movement’s debate about disruption gets wrong. By Kevin A. Young & Laura Thomas-Walters in Nature: Humanities and Social Sciences Communications (Jan 2, 2024).

From throwing soup to suing governments, there’s strategy to climate activism’s seeming chaos − here’s where it’s headed next. By Shannon Gibson in The Conversation. (Feb 2, 2024)

🗃️ From the Archive

“If you say that a plant “learns,” “decides,” “communicates,” or “remembers,” are you humanizing the plant or vegetalizing a set of human concepts? The human concept might take on new meanings when applied to a plant, just as plant concepts might take on new meanings when applied to a human: blossom, bloom, robust, root, sappy, radical…”

– Merlin Sheldrake, in Entangled Life: How Fungi Make Our Worlds, Change Our Minds & Shape Our Futures

🌊🐢Sea Turtles!

Now that my book exploring language and communication at the nexus of sea turtle conservation and tourism in Hawai‘i is finally out (I'm hoping to make it free access next year so stay tuned!), I thought this would be a good occasion to start up a brief section here at the end of the digest sharing sea turtle-specific events, news, and research for those who might be interested. And I'm still waiting for Apple to create a sea turtle icon, so until that day I'll have to improvise with an ocean turtle combo (🌊🐢) . Anyways, here's an interesting piece on the impacts of sea turtle tourism in Barbados:

Should Tourists Swim with Endangered Sea Turtles?: Researchers in Barbados found that ecotourism sea-turtle encounters created some very human problems for the animals. By Jeff Platt in the Revelator.

And the research article it discusses: Effects of “swim with the turtles” tourist attractions on green sea turtle (chelonia mydas) health in Barbados, West Indies.

💬 Quotes I’m thinking about

“I come to the present, to who I am, by a different route from yours; and therefore, our conversation has to recognise that different histories have produced us, different histories have made this conversation possible. I can’t pretend to be you. I don’t know your experience. I can’t live life from inside your head. So, our living together must depend on a trade-off, a conversation, a process of translation. Translations are never total or complete, but they don’t leave the elements exactly as they started.”

–Stuart Hall In Living with difference: Stuart Hall in conversation with Bill Schwarz (2007, p 151).

Thanks so much as always for your interest in my work, and if you found this digest useful, please consider sharing with others who might find it interesting too😊 I'd also love to hear from you. Leave a comment to let me know what you think about this digest, what areas of environmental communication you’re involved in/most interest you, or anything you’d like to see more of in Wild Ones:)

If you found this newsletter useful in your own life and work, consider subscribing to receive future Wild Ones posts in your inbox. Wild Ones will always be a free educational resource, but if you’d like to support my writing, consider a paid subscription option too:)

On a side note, when I was reading about this doppelganging process, I couldn’t help thinking about the sociologist Erving Goffman’s dramaturgical ideas about ‘the presentation of self in everyday life,’ especially his chapter on ‘discrepant roles’ where he discusses all the forms of ‘information control’ and splintering of ‘backstage’ and ‘frontstage’ selves that people engage in in everyday interaction to (mis)represent and perform the most useful/beneficial versions of themselves for a particular situation, whether in an argument, a meeting or a public speech. I think Goffman’s work can be an important source of insight for thinking about digital doppelganging in the age of TikTok and X.